Breaking the Cycle: Effectively Addressing Homelessness and Safety

Authors

Table of Contents

Media Contact

For general and media inquiries and to book our experts, please contact: pr@rstreet.org

Executive Summary

This paper responds to municipalities’ concerns about the increase in visible homelessness and its perceived impact on community safety. The overlap between the criminal justice system and homelessness is well-documented, but debates on how to best address these issues remain divisive. Many stakeholders entrenched in their viewpoints, often overlooking the complexity of homelessness and the need for a multifaceted approach. However, the reality is that singular solutions have proven insufficient. We must combine strategies and offer multiple options to address the diverse needs of different individuals.

Arrest and jail should always be a last resort for addressing homelessness, as criminalizing survival behaviors only perpetuates the cycle of homelessness and incarceration. This approach is costly, can be harmful, and fails to address the underlying causes of homelessness. To break this cycle, it is crucial to find better solutions, some of which we explore in this piece.

Key conclusions:

- Immediate Actions: Providing jobs—such as trash cleanup in an encampment—to homeless individuals, managing public spaces, and offering safe parking lots for those living in vehicles can prove impactful. Additionally, involuntary hospitalization and scattered sites programs can offer immediate support to those needing urgent assistance. Homeless outreach teams can also play a crucial role by building trust, offering immediate assistance, and connecting individuals to essential services, ultimately reducing reliance on emergency services and jails.

- Long-Term Strategies: Expanding transportation and housing options is critical for reducing homelessness, as doing so provides greater access to jobs and shelter. Innovative solutions like using vacant hotels for immediate housing, employing community courts for rehabilitative justice, creating “one-stop shops” for essential services, and using shelter-finder apps can help stabilize individuals and connect them to necessary resources.

- Early Intervention: Providing financial training and support equips individuals with the skills to manage money effectively and plan for major life events, which can help prevent one setback from snowballing into homelessness. Predictive analytics can identify at-risk individuals before eviction, enabling targeted early intervention to stabilize their housing situation. Expanding supportive housing and improving access to mental health and substance use treatment are crucial for those transitioning from incarceration or facing behavioral health challenges. Efforts like the Clean Slate Initiative and the creation of “third places” help reintegrate individuals into society and build community-support networks.

Introduction

Imagine walking through streets lined with makeshift shelters, discarded needles, and trash. For many, this is the image that comes to mind when they hear the word “homelessness.” In cities today, individuals are becoming unhoused at an alarming rate, and community members are feeling increasingly unsafe. In response, city officials struggle to address these issues in a way that is both effective and humane.

Now imagine being labeled as part of the problem rather than as a valued member of the community. Whether they are living on the streets, in a shelter, or in a budget motel, homeless individuals are likely facing more dangerous conditions, worse health outcomes, and fewer opportunities than their housed neighbors. These individuals may suffer from undiagnosed mental health disorders or may have turned to drugs or alcohol to cope with past or current traumas. Unfortunately, access to mental health services and addiction support is often limited or unavailable, and the threat of incarceration is a constant concern. Quality of life for homeless individuals is often dire, characterized by higher mortality rates, frequent victimization, and a greater likelihood of arrest. Jails have become de facto mental health facilities, homeless shelters, and detox centers, underscoring the severity of the issue. Upon release from jail, rather than finding stability, many are returned to the same harsh environment with even fewer resources than they had before incarceration, perpetuating the cycle of homelessness and despair.

For too long, decision-makers have merely focused on reducing the visibility of homelessness. As a result, homeless individuals are often viewed as separate from the community, even though they are interwoven in it. Cities must shift their focus to find ways to support this vulnerable population and help individuals climb out of homelessness, while also addressing community concerns about safety, disorder, and sanitation. To effectively reduce homelessness, cities need both immediate and sustainable solutions. Unfortunately, many cities’ stakeholders are divided over best strategies, which is stalling progress. Instead of debating the merits of strategies to manage and mitigate homelessness, policymakers must prioritize this population to drive lasting positive change in overall community well-being and sense of safety.

This paper explores the interconnected issues of homelessness and safety, examining both immediate interventions and long-term strategies that can help achieve sustainable change. We analyze the current crisis, explain how we arrived here, identify currently debated approaches, and provide alternative solutions that balance compassion with practicality. Through this comprehensive approach, we aim to offer a roadmap for cities to build safer, thriving, inclusive communities.

Today’s Crisis

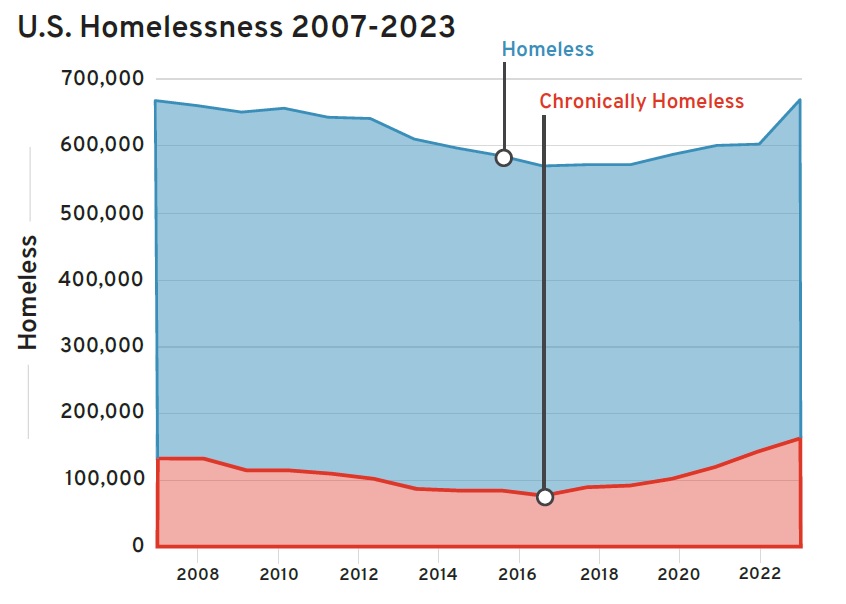

As cities nationwide struggle with growing rates of homelessness, the issue has become increasingly noticeable, with more individuals living on the streets or in encampments. This visibility has intensified concerns about crime and unrest in communities. For homeless individuals, survival is a daily challenge as they navigate the dangers and hardships of life on the streets. This includes finding food, shelter, and safety, often in environments that are hostile and unwelcoming. Those on the verge of homelessness also face challenges to stay afloat as existing systems fail them. Understanding the current homelessness crisis, visualized in Figure 1, from different perspectives is important to creating solutions that address both immediate needs and root causes of this crisis.

Figure 1: U.S. Homelessness

portal/sites/default/files/pdf/2023-AHAR-Part-1.pdf.

Homelessness encompasses a range of nonpermanent living situations that are often categorized and tracked as either sheltered or unsheltered. Sheltered homelessness refers to temporary respite that does not offer a permanent solution, such as emergency shelters or transitional housing. Unsheltered homelessness involves individuals living in places not meant for human habitation, such as streets, parks, vehicles, or abandoned buildings. Those living in a low-budget motel, on a friend or family member’s couch, or in other night-to-night situations are often not captured in either definition or in data collection.

Chronic homelessness is another critical concept within this context. It typically refers to individuals who have experienced homelessness for an extended period, such as a year or more, or have had multiple episodes of homelessness over several years. These individuals frequently have disabling conditions or disorders that complicate their ability to maintain stable housing.

The faces of homelessness are diverse and varied. Here are some examples:

Table 1: Faces of Homelessness

| Single female with kids, unsheltered: For most of her life, she struggled with the complexities of mental illness and poverty, experiencing severe insomnia, night terrors, impulsivity, and deep depression. Her challenges escalated in her mid-30s when she began using methamphetamine to cope while working long hours as a truck driver and supporting her children, which eventually led to homelessness and loss of custody. Despite showing signs of mental illness for years, she was not diagnosed until she was in her early 50s. |

| Family of five, motel/squatting: A hardworking husband and father of three, he has been unhoused despite being steadily employed as an apartment maintenance worker. Although living in a motel is essentially a form of homelessness, it did not meet the official definition, which prevented him from accessing long-term financial assistance. Motels are expensive and, without financial assistance, he could no longer afford to keep his family there. His family is now squatting in a vacant apartment owned by his employer, hoping for a stable place to live. |

| Single male, couchsurfing/unsheltered: After losing both of his parents and brother to cancer in a short time, he ended up homeless and turned to drugs and alcohol out of anger and grief. At times, he was fortunate enough to sleep on a friend’s couch, especially when it was cold, but otherwise found himself living on the streets. |

| Single, full-time student, car-living/shelter: She was a full-time student living at home with her mother, a veteran dealing with mental health issues. Her mother was institutionalized, and the bank began foreclosure on their home. Without a place to live and unprepared for the sudden loss, she started living in her car and then ultimately found a shelter. |

| Single male, car-living: He became homeless after his college football career abruptly ended due to a neck injury. Struggling to cope with the loss of his athletic career, he grew bitter and strained his relationships. After being fired from multiple jobs and battling cancer, he found himself living in a van behind a car wash. |

Key Data on U.S. Homelessness

Over the past decade, the number of individuals experiencing homelessness in the United States has fluctuated because of a variety of factors such as economic conditions, public health priorities, environmental factors, and public policy priorities. In 2023, over 653,000 individuals experienced homelessness on a given night, marking the highest number recorded since the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development began their “point-in-time” count in 2007. Nearly 40 percent of those individuals were unsheltered, and 31 percent were chronically homeless, both of which contributed to the growing visibility of homelessness in cities. Families with children and unaccompanied youth saw the greatest increases from the previous year. Sixty-three percent of the homeless population resides in just seven states—California, New York, Florida, Washington, Texas, Oregon, and Massachusetts. The number of additional people who are at risk of becoming homeless and often living in unstable housing situations remains unknown.

Behavioral Health

The relationship between behavioral health issues and homelessness is well-documented. Some estimates show that nearly one-third of unhoused individuals have severe mental health disorders, and one-quarter have substance use issues. The rate of alcoholism is likely even higher. However, the relationship between behavioral health issues and homelessness is more complex than statistics alone can capture. For example, stigma and undiagnosed disorders likely lead to an underestimation of the scope of the correlation. Further, the direction of causality between homelessness and behavioral health issues is unclear. The overwhelming majority of people living with mental health disorders and most individuals using drugs or alcohol do not become homeless. It is therefore unclear whether mental health challenges or overuse of substances more commonly lead to homelessness or if the stress and trauma of homelessness are more likely to contribute to substance use, severe depression, or other mental health problems.

Economic Challenges

Homelessness has significant costs that extend beyond individual hardships and the provision of shelters and services. It is estimated that the United States spends billions of dollars annually on homelessness. Emergency room visits and hospitalizations for homeless individuals are frequent and expensive, often due to untreated chronic illnesses, mental health issues, and substance use disorders. Law enforcement and incarceration costs also escalate as homeless individuals are frequently arrested for survival offenses, such as trespassing in a building to stay warm or defecating or urinating outside. Furthermore, some believe visible homelessness hurts the profits of nearby businesses, negatively impacting small business owners and reducing tax revenue that could be reinvested into the community.

Perception

Many attribute the rise in perceived crime to growing rates of unsheltered and chronic homelessness and the social disorder they represent. This perception is not based on actual crime statistics, but it is deeply influenced by the visibility of homelessness and associated behaviors. While it is true that rates of some criminal offenses spiked following COVID-19 closures and periods of civil unrest like after George Floyd’s murder, overall crime has decreased over the past few years while rates of homelessness have continued to increase. Still, the presence of encampments in public spaces, open air drug use, and the frequent sight of individuals in mental health crises can make areas feel less safe—even if crime rates tell a different story. Homeless individuals are also intertwined with the criminal justice system at much higher rates than the general population, adding another layer of complexity to the situation.

How We Got Here

The history of homelessness in the United States is long and complicated. Homelessness, which briefly waned following the Civil War, surged into the national spotlight by the late 1800s. This increase was fueled by the rapid growth of the national railroad system, the boom of urbanization, and a growing dissatisfaction with the harsh conditions of industrial labor. During the Great Depression, mass unemployment and poverty led to widespread homelessness, giving rise to “Hoovervilles” or shantytowns. In the post-World War II era, economic prosperity and social safety nets reduced visible homelessness.

Over the next three decades, the face of homelessness remained predominantly white and male, but grew older. Many lived in the cheapest accommodations in the poorest urban areas—such as flophouses and low-cost motels—which by today’s standards would be considered “sheltered” or even “housed.” Others joined encampments that were concentrated in urban areas, often referred to as “Skid Row.” In many ways, the visibility of homelessness faded or shifted out of general public view. However, by the late 1970s, a more modern form of homelessness emerged—one that appeared to be affecting a younger population and involving more women, children, and minority groups.

In the 1980s, the country experienced one of its worst recessions since the Great Depression. Over the next decade, this economic downturn, coupled with deinstitutionalization, watershed events, and urban gentrification, led to a resurgence in homelessness. Property values rose in many urban areas, and low-cost nightly housing options disappeared, resulting in the removal of approximately 4.5 million housing units, half of which were occupied by low-income households. Meanwhile, HIV/AIDS emerged, driving up medical costs in many marginalized communities, and a rise in crack cocaine use and the subsequent War on Drugs devastated entire neighborhoods. In addition, many veterans who returned from the Vietnam War, often with disabilities and high rates of opioid dependence, found themselves on the streets. Simultaneously, the shuttering of state mental health hospitals in the prior decades led to a drastic reduction in institutionalized residency and care, with the number of patients in such facilities plummeting from 535,000 in 1960 to 137,000 in 1980, leaving many without shelter. The economy was also shifting from manufacturing to lower-wage service jobs. With over three-quarters of new jobs starting at minimum wage, more than 15 percent of Americans were living below the poverty line. At the same time, federal funding for affordable housing and social programs for low-income families was cut by $57 billion in just three years.

Thus, the 1980s triggered a perfect storm that led to a 400 percent increase in the number of people experiencing homelessness during the decade. This sharp increase suggests that homelessness is not just a result of individual circumstances; broader societal factors are at play.

The 2000s saw some stabilization in rates of homelessness even following the Great Recession of 2007-2009, which caused a surge in foreclosures, evictions, and unemployment. However, homelessness has only worsened since 2016, with each year showing a steady rise in overall numbers, including a sharp increase in unsheltered and chronically homeless individuals.

Some believe that homelessness is not the core issue but rather a symptom of deeper, underlying problems. Economic instability, driven by a range of personal circumstances, can force individuals and families into unstable housing situations. The added pressure of transportation and childcare needs can further strain their ability to maintain income, leading to increased housing instability. Systemic problems, such as economic inequality, a lack of affordable housing, and inadequate mental health and addiction services, are also factors.

Below, we highlight individual and societal factors that may put someone at risk of homelessness. It is important to note that the direction of causality between these issues remains unclear; it is also possible that other underlying factors contribute to both rather than one directly causing the other.

Table 2: Potential Contributing Factors to Homelessness

| Incarceration | -Individuals imprisoned once are nearly seven times more likely to be homeless; those imprisoned multiple times are 13 times more likely. -More than half of those experiencing homelessness have a history of incarceration. -Thirty-three percent of homeless children have an incarcerated parent. |

| Domestic Violence | -Domestic violence is the direct cause of homelessness for 22 to 57 percent of homeless women. -Over 80 percent of homeless mothers with children have previously experienced domestic violence. |

| Foster Care | -Between 31 and 46 percent of youth aging out of foster care become homeless at least once by age 26. |

| Military Service | -Veterans make up 7 percent of the U.S. population but nearly 13 percent of the homeless adult population. -The number of homeless veterans has decreased by approximately half since 2009. |

| Identification as LGBTQ+ | -Up to 40 percent of homeless youth identify as LGBTQ+. -LGBTQ+ adults are twice as likely to have experienced homelessness as the general population. |

| Mental Health Disorders | Studies show that certain disorders are more prevalent among people experiencing homelessness, such as: -Schizophrenia spectrum disorders (7 to 12.4 percent) -Major depressive disorder (12.6 to 19 percent) -Antisocial personality disorder (26 percent) -Bipolar disorder (8 percent) |

| Substance Use Issues | Homeless individuals commonly experience the following substance use disorders: -Alcohol use disorders (36.7 percent) -Drug use disorders (21.7 percent) -Substance use disorder (44 percent) |

| Medical Issues | -Traumatic brain disorder is found in 53.1 to 71 percent of homeless individuals. -Shelter residents are more than twice as likely to have a disability as the general population. -Medical debt plagues approximately two-thirds of individuals facing eviction or foreclosure. |

| Housing Costs | -When households spend over 32 percent of their income on rent, communities often see a sharp rise in homelessness. -A $100 increase in median rent is linked to a 9 percent rise in the estimated homelessness. |

Crime, Safety, and Homelessness Connection

Understanding the full relationship between homelessness and crime is difficult because most law enforcement agencies and prosecutor offices do not consistently collect data on homelessness for victims or the accused. The research that does exist generally reveals a harsh truth that homeless individuals are disproportionately involved in the criminal justice system.

Homeless living conditions are subject to the same factors that drive criminal activity in other parts of the city, but at an intensified level. Crimes often occur between familiar parties and in densely populated areas, which can have a significant impact on the close-knit dynamics of homeless encampments and shelters. Research indicates that certain mental health disorders, such as schizophrenia and severe depression—which are more prevalent within the homeless community—may contribute to higher crime rates. Similarly, the misuse of drugs or alcohol, which is also more common among the homeless population, shows a potential link to increased criminal activity.

While there is a dearth of national data, statistics from individual cities reveal alarming trends. In San Diego, homeless individuals are 514 times more likely to be arrested for felonies, often having multiple criminal cases simultaneously. Similarly, in Los Angeles, despite making up just 1 percent of the population, homeless individuals are suspects in 6 to 8 percent of all crimes and in 11 to 15 percent of violent crimes. While these statistics are concerning, limited data and lack of comprehensive analysis mean they should be interpreted carefully. For example, other studies offer a different perspective, suggesting that homeless encampments have minimal impact on the actual number of property crimes and that the rise in property crime reports is more strongly linked to growing complaints about homelessness. This is because homeless individuals can often be subjected to heightened public scrutiny due to visible mental health crises and open-air drug use, and, thus, more frequently the subject of police calls.

Of course, homelessness is often directly criminalized through laws that target survival behaviors like loitering, panhandling, and sleeping in public spaces. Additionally, crimes committed out of necessity, such as stealing basic necessities or trespassing to stay warm, contribute to a cycle of displacement, fines, and incarceration. As a result, it is estimated that homeless individuals are 11 times more likely to be arrested than the general public.

It is important to recognize that crimes committed by the homeless represent only a small fraction of overall crime, and homeless individuals are far more likely to be victims than suspects. For example, statistics from San Diego and Los Angeles not only revealed higher arrest rates among the homeless, but also showed much higher rates of victimization. In San Diego, homeless individuals are 19 times more likely to be murdered, 27 times more likely to face attempted murder, and significantly more vulnerable to assault and sexual violence. In Los Angeles, nearly 60 percent of homeless women reported theft, over 40 percent experienced harassment and threats, 35 percent suffered physical assaults, and 20 percent endured sexual violence. Unfortunately, after being victimized, homeless individuals may be more likely to commit crimes in the future, potentially as an act of retaliation, as a means of preemptive self-defense, or as a result of their inability to access resources for their own trauma.

In addition to contributing to the growing jail population, homeless individuals often find themselves without stable housing upon release. This is problematic because even one day in jail could lead to the loss of employment, temporary housing, or custody of children. Loss of employment further challenges their ability to pay the high costs of prosecution and restitution, starting people off at an even greater disadvantage as soon as they are released.

These issues are exacerbated by the fact that, if arrested, homeless individuals may spend more time in jail because of fears of failure to appear and an inability to secure bail. They also have a higher risk of triggering a technical violation of probation and parole, leading to potential reincarceration. Having a history in the criminal justice system can create barriers to employment and housing due to stigma and legal restrictions. Further, issues that affect the incarcerated population at greater rates—such as substance misuse or severe mental illness—can either disqualify individuals from accessing certain types of supportive housing or make it effectively inaccessible because of an inability to follow through on all requirements. As a result, formerly incarcerated individuals are nearly 10 times more likely to experience homelessness than the general population.

How SCOTUS Has Shaped the Issue

The Supreme Court has addressed different aspects of the criminalization of homelessness. Table 3 is a historic overview of key cases that have shaped the legal landscape on this issue. It is important to recognize that while certain actions may be deemed legally “constitutional,” they may not be considered the most effective or just solutions.

Table 3: Supreme Court Cases

| Issue | Case | Holding |

| Status Crimes | Robinson v. California (1962) | The Supreme Court ruled that a California law making it a crime to be addicted to narcotics was unconstitutional. The Court found that punishing someone for their status of addiction, rather than for a specific behavior, violated the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment. There has been debate of how this ruling applies to anti-homeless laws. |

| Anti-Loitering Laws | Chicago v. Morales (1999) | The Supreme Court struck down a Chicago ordinance that made it illegal for individuals to loiter if ordered to move by police. The Court found the law to be unconstitutionally vague because it did not clearly define what behavior was prohibited, leading to arbitrary enforcement and potentially violating individuals’ due process rights under the Fourteenth Amendment. |

| Anti-panhandling Laws | Reed v. Town of Gilbert (2015) Thayer v. City of Worcester (2015) | The Reed decision established a stricter standard for determining whether First Amendment laws regarding signs are content-neutral, meaning that laws targeting specific types of speech are more likely to be considered unconstitutional. As a result, many panhandling laws, which often contain speech asking for money, have been challenged and struck down because they are seen as content-based regulations. The Thayer decision further reinforced this by the Supreme Court requiring the lower court to reevaluate their panhandling law decision in light of the Reed standard. |

| Anti-camping Laws | City of Grants Pass v. Johnson (2024) | The Supreme Court found that an Oregon city’s ordinances banning camping in public spaces did not violate the Eighth Amendment’s Cruel and Unusual Punishments Clause because they targeted the act of camping, not the status of being homeless, and the penalties were neither cruel nor unusual. |

Competing Perspectives on Solutions

The debate over how to address homelessness has intensified in recent years as the crisis has continued to grow and become more visible. This debate centers on several key approaches—each with its own supporters and critics—that can be implemented either independently or in combination: Housing First, Treatment First, and the use of legal enforcement.

Housing First

Housing First has been widely used since the early 2000s when President George W. Bush adopted the initiative as part of the National Policy to End Homelessness. This approach prioritizes providing permanent housing to homeless individuals as the initial step, without requiring them to address other issues like addiction or mental health before receiving housing. This is grounded in the belief that stable housing serves as a foundation, and is therefore a prerequisite, providing individuals with the stability they need to address other challenges. Once housed, individuals are often offered voluntary support services, such as substance abuse disorder treatment, mental health care, and job training, which they can engage with at their own pace. Housing First has gained significant support because some studies show positive outcomes with stable housing, including fewer hospitalizations. However, evidence is mixed for other outcomes, such as improvement of behavioral health issues. Critics also argue that Housing First may attract or retain individuals in the homeless system with the promise of free, permanent housing, and success data may be misleading because it reclassifies living situations instead of tracking real change. Further, while this strategy initially led to a decline in homelessness, the number of unhoused individuals has risen steadily since 2016.

Treatment First

Before the 2000s, the Treatment First model was the primary approach used when homelessness rates were at their peak. This model focuses on the need for individuals to address issues like substance use or mental health disorders before or as a requirement to receiving housing. Proponents argue that without addressing these root causes, housing alone cannot lead to long-term stability. This approach relies on external motivators to encourage individuals to engage in treatment, asserting that achieving sobriety or stable mental health will result in gaining employment and housing. It is frequently used within the criminal justice system through efforts like diversion or problem-solving courts. Critics, however, argue that the stress of living on the streets makes it nearly impossible to succeed in treatment and that forcing treatment is ineffective at best and harmful at worst. Additionally, it is not productive to require that individuals initiate treatment when their substance use may not be an addiction, but rather a coping mechanism for their circumstances.

A key point of contention between these approaches is the effectiveness of voluntary versus mandatory treatment. Research outcomes vary, with some studies showing better results for voluntary treatment due to higher engagement and willingness to participate, whereas others suggest that mandatory treatment can be effective in providing access to necessary care for those who might not seek help on their own. Interestingly, one study found that individuals who might face involuntary commitment strongly supported it for mental health or drug issues when used to prevent harm to self or others or to reduce crime. Varying metrics of “success”—such as achieving sobriety, maintaining stable housing, or securing employment and non-subsidized housing—could explain differing results.

The Role of Enforcement

Whether housing or treatment should come first is not the only debate. The role of enforcement measures like encampment sweeps, where local governments clear out homeless encampments from public spaces, and policing or court authority also is highly contested. While these tactics are often used in conjunction with a Housing or Treatment First model, they have also been used alone, resulting in displacement or jail. Some believe that in certain circumstances, especially in urban areas where encampments can lead to unsanitary conditions, crime, and public nuisance, more forceful measures are necessary to protect public health, safety, and order. However, there is a fear that these measures harm homeless individuals and are a waste of resources. The term “sweep” alone suggests treating people as if they are trash, rather than recognizing them as members of the community.

Many cities use encampment sweeps to reduce the spread of disease, clean up commercial areas, and reduce pollution. Some believe that sweeps can also help connect individuals with shelters or treatment programs while reclaiming public spaces for broader community use. Critics, however, argue that sweeps often displace people without offering viable alternatives, thereby moving—but not fixing—the problem. Further, sweeps can destroy personal belongings and important records and traumatize those experiencing homelessness, making it even harder for them to access services and stabilize their lives.

Anti-camping and anti-sleeping laws, sometimes associated with sweeps, allow municipalities to arrest, fine, or forcibly move homeless individuals from public spaces. More recently, cities have been turning to civil commitment statutes, which let them involuntarily hospitalize someone based on their mental health or substance use conditions. These statutes are typically used when someone poses a danger to themselves or others, but their application has been expanded in some states. Similarly to sweeps, proponents argue that these laws help maintain public order and address safety and health concerns within communities. They also contend that legal intervention can be a necessary first step in connecting people to services and treatment, especially if they were previously unable or unwilling to seek help. In fact, some individuals have claimed that incarceration “saved their life.” Critics argue that using legal force not only violates the civil liberties of homeless individuals but is also an inefficient and costly approach to what is fundamentally a public health issue. Further, placing someone in jail or an involuntary treatment facility can deepen the cycle of homelessness by creating legal and financial barriers to recovery.

While the debate over how to best address homelessness continues, it is evident that all sides share a commitment to finding an effective solution. However, the intensity of the debate has led to entrenched positions, making it harder for individuals to consider alternative approaches, compromises, or innovative solutions.

Bridging the Divide

To effectively address homelessness, policymakers must first clarify the primary problem they aim to solve. This means understanding the “why” before determining the “how.” In other words, they must define what success looks. Without a shared vision, prioritizing resources and evaluating outcomes becomes quite difficult. As with most issues, every solution involves trade-offs, so policymakers must carefully consider how different approaches will affect community needs.

For example, if some policymakers view success as reducing the number of visible homeless individuals on the streets, they might favor policies that remove people from public view rather than addressing the underlying issues that contribute to homelessness. Others, however, may define success by the number of individuals who move into stable housing or engage in treatment but might consider the costs of programs or long-term self-sufficiency. Without a shared understanding of what success looks like, efforts to tackle homelessness can become disjointed and conflicting, ultimately hindering progress and leaving many needs unmet.

When evaluating solutions for those living on the streets, several considerations are important to any goal or solution:

- What is most humane—Overlooking people in need is neither a viable nor compassionate response, particularly when many unsheltered individuals suffer from conditions that severely limit their ability to care for themselves. The challenge lies in balancing respect for individual autonomy with the government’s responsibility to support those who are unable to care for themselves. Allowing individuals to live on the streets without government intervention may respect their freedom, but it also exposes them to significantly higher rates of violence, trauma, and mortality. On the other hand, criminalizing homelessness or forcing treatment might provide immediate intervention, but it may only conceal a problem rather than produce lasting results, or it may even perpetuate a harmful cycle of incarceration and homelessness. Prioritizing sustainable solutions over quick fixes to improve the health, safety, and living conditions of those experiencing or at risk of homelessness will ultimately strengthen cities, fostering a sense of safety and inclusivity for everyone.

- Fear of Crime—Many believe that the visible presence of homelessness is making communities feel unsafe, regardless of whether that danger is real or perceived. The perception of being unsafe can harm cities by weakening social cohesion, which is necessary for community well-being, and this, in turn, can exacerbate community distress. This sense of danger can also deter economic investment, leading to lower property values and diminished business activity, further contributing to an area’s economic decline. Additionally, it can stigmatize vulnerable populations, such as the homeless, fostering further division rather than empathy. Over time, this perception can drive people to move away, making it harder for the community to recover and thrive. Thus, the public’s response to the perceived impact of homelessness on safety could turn perception into reality, making it an essential issue to address.

- Prioritize Behavioral Health—It is widely recognized that behavioral health issues are a nationwide problem that disproportionately affect homeless individuals. The co-occurrence of mental health disorders and substance use has also been shown to increase the likelihood of arrest. Thus, finding ways to improve well-being throughout the community would be beneficial for both homeless populations and the general public. Improving access to treatment, whether through voluntary or mandatory programs, is a key step in tackling these problems. However, barriers to treatment, such as limited availability of services, stigma, and financial constraints, continue to pose significant obstacles.

- Prevention—Many discussions about homelessness focus on the most visible populations, such as unsheltered and chronically homeless individuals. However, a broader definition of homelessness can also include a growing number of community members who are barely getting by. While efforts often center on addressing homelessness after it occurs, preventing people from becoming homeless is just as important. Prevention measures could not only help combat homelessness, but could also benefit the community as a whole.

Moving Beyond the Cycle

The revolving door between homelessness and incarceration is another issue that must be addressed. The ineffective and harmful pattern currently in place fails to tackle the deeper complexities of homelessness and wastes public resources that could be better allocated toward long-term solutions. However, non-legal, single-issue approaches also fall short.

The increase in chronic homelessness and the proportion of people newly experiencing homelessness is troubling. This trend calls into question Housing First as a standalone solution. Because Housing First is designed as an intervention for those already experiencing homelessness rather than as a preventive measure, it likely has little impact on avoiding new cases of homelessness and struggles to keep pace with the growing number of people becoming homeless. Further, while Housing First offers immediate relief by securing housing, it may not fully address the broader, more complex individual factors that contribute to homelessness or the societal issues that complicate maintaining housing.

However, treatment without housing is also likely to be unproductive on its own. Many challenges beyond behavioral health issues—such as earning a livable wage, securing reliable transportation, and maintaining access to childcare—contribute to someone being able to make the transition from street to home. Addressing only one aspect of the problem is like trying to plug a single hole in a sinking ship full of leaks. Further, it is important to remember that experts estimate that more than half of homeless individuals do not have severe behavioral health issues. This suggests that access to housing is a crucial component of any effective solution.

Allowing legal interventions in extreme cases should also be considered as part of a comprehensive strategy, rather than in isolation. The criminal justice system’s role in addressing homelessness is a delicate balance; it can either work collaboratively to address the issue or inadvertently contribute to it. A strict law-and-order approach to homelessness, which is deeply connected with public health and social issues, is likely to be ineffective. However, law enforcement, along with prosecutors and courts—who have long been involved in addressing the needs of the unhoused—can play a crucial role in creating effective solutions.

Therefore, a blended and individualized approach may offer the best solution. For some, immediate, unconditioned housing is helpful. For others, it may be necessary to address underlying issues like mental health or substance use in conjunction with providing a safe place to stay. And still others may need long-term, supportive, subsidized housing due to physical or mental disabilities. Tailoring interventions to individual needs rather than applying a standard approach to all can lead to better outcomes. For example, younger individuals, often lacking job skills and stable support networks, may benefit from education, job training, and voluntary connection to services. In contrast, older adults may face chronic health issues and mobility challenges that require healthcare access, senior-specific housing, and long-term support services. Additionally, individuals with substance use disorders may require more flexible living arrangements and treatment strategies (e.g., such as harm reduction strategies, rather than strict sobriety requirements). However, in some cases where criminal behavior is involved, the added motivation of legal consequences may be necessary to encourage positive change.

While it is commonly believed that services are available for those experiencing homelessness, accessing these limited resources can be extremely challenging. Individuals seeking help often face long waitlists and uncertain communication, as well as logistical hurdles like transportation issues and the need to travel across the city to reach various service providers, many of whom are open only during specific hours. Having to bring all of one’s belongings to appointments, risking losing one’s spot in the waitlist, and balancing these challenges with the needs of children can make accessing support nearly impossible.

With nearly two-thirds of Americans reporting that they live paycheck-to-paycheck, it is crucial to look at early intervention and strategies to prevent homelessness. For too many, a few strokes of bad luck or a single bad decision could push them into homelessness. By finding ways to better support those on the brink of losing their homes and addressing their issues before they escalate to homelessness, cities could effectively reduce the number of people who become unhoused.

Cities struggling to address homelessness need immediate, actionable solutions. Table 4 highlights some of the innovative and promising strategies that target underlying factors of homelessness and that can create positive long-term outcomes.

Table 4: Immediate Actionable Solutions

| Action | What is it? | Why is it needed? |

| Provide jobs within encampments | Providing jobs to homeless individuals to help clean up encampments or other areas as well as get connected with services. | Including homeless individuals in the solution can help them reengage with society and access vital resources. |

| Coordinate public-space management | This includes regulation, management, and interventions in public spaces. This could encompass providing regular trash pick-up, safe drinking water, public restrooms, and trained outreach staff to help with disputes and connect individuals to services. | Public-space management helps create safer and more orderly environments for both housed and unhoused community members. It also helps connect homeless individuals to resources, such as shelters, health care, and social services, thereby facilitating better support and more sustainable solutions for those experiencing homelessness. |

| Offer safe parking lots | A safe parking lot is a designated area where homeless individuals can safely and legally park their cars overnight. Such places may also include case management. | Safe parking lots for homeless individuals are needed to provide a secure place for those living in their vehicles, offering protection from harassment, access to basic amenities, and a stable location from which they can access services. |

| Establish a city-wide shelter finder | An app that provides outreach workers and others with real-time information on available shelter beds that match the needs of homeless individuals. | This allows outreach workers to quickly and efficiently connect people with appropriate housing options. It improves their chances of finding immediate shelter, reduces the time spent searching for resources, and ensures that individuals receive the specific support they need. |

| Allow for involuntary hospitalization | Though most states already have involuntary commitment statutes, their scope may be different. Involuntary commitments allow for someone who is incapable of taking care of themselves to be held temporarily so that they can regain their competence. This tool should be used only in the most extreme cases, such as those that are chronically unsheltered and suffer from severe traumatic brain injury, schizophrenia, or the most extreme substance use disorders. Further, individuals must be able to access support to make this solution effective. | Involuntary hospitalization can be beneficial for those with severe behavioral health issues because it ensures they receive immediate care and support when they are unable to make decisions for themselves. In extreme cases, this intervention can prevent harm to the individual and others, provide stabilization, and offer access to necessary treatment and resources that might not otherwise be sought voluntarily. |

| Implement scattered-site programs | This program places homeless individuals and families in privately owned rental units throughout the community, funded by government-issued vouchers. It also offers supportive services and case management to help residents maintain stability and achieve self-sufficiency. | This type of program is beneficial because it uses already-available private rental housing, eliminating the need to develop new housing or take over existing properties. By leveraging existing rental units, the program can quickly house individuals and families in units that best fit their needs. Additionally, integrating residents into the community helps promote social inclusion. |

| Establish homeless outreach teams | Specialized law enforcement teams assist homeless individuals, sometimes as co-responders or alongside crisis intervention teams. They focus on connecting with homeless individuals and building relationships with service providers, rather than making arrests. | Police are frequently called to handle homelessness-related issues. Establishing specialized teams for this purpose can build trust and relationships with the homeless community. These teams can better address specific needs, provide immediate support, and connect individuals to necessary services, thereby reducing the burden on emergency services and jails. |

Table 5: Promising Long-Term Strategies

| Action | What is it? | Why is it needed? |

| Expand transportation options | This could involve offering discounted transit fares for low-income individuals, increasing access to dockless e-bikes and scooters, or expanding public transportation routes to underserved areas. | A study found that access to transportation is the biggest factor in escaping poverty and avoiding homelessness. While some people benefit from extensive metropolitan transit systems, many do not. Further, drivers have significantly more job opportunities than those relying on public transit, especially low-wage workers with irregular hours. |

| Support affordable housing | Cities are becoming more innovative in creating affordable housing. These efforts include using 3D printing technology, employing AI to automate structural design, and changing policies to reduce single-family zoning restrictions. | The United States faces a 7.3-million-unit shortage of affordable and available rentals for extremely low-income renters. Research consistently shows a connectionbetween housing costs and homelessness, indicating that homelessness increases when rents rise beyond what low-income households can afford. |

| House homeless individuals in hotels | Some cities have used vacant hotel rooms to house homeless, whereas others have bought entire vacant hotels to use as shelters. These options can provide a safer and more private option for homeless individuals, especially families, compared to shelters. | Housing homeless individuals in hotels offers immediate shelter, safety, and stability, while also providing access to essential services and buying time to find permanent housing solutions. |

| Establish homeless/community court | Homeless and community courts allow individuals experiencing homelessness to resolve warrants and criminal cases by participating in services through community providers, often resulting in case dismissal. These sessions are typically held at accessible locations outside of traditional courthouses. | This approach addresses the legal issues of homeless individuals by focusing on rehabilitation instead of punishment, connecting them with social services, housing, and treatment programs to resolve minor offenses, promote stability, and reduce recidivism, which benefits homeless individuals and the broader community. |

| Organize one-stop shops | “One-stop shops” consolidate resources that homeless individuals frequently need, reducing barriers to services, support, and care. These can be established as brick-and-mortar locations with satellite offices for various programs or organized as one-day or seasonal events. Some cities have also included clearing warrants in such events. | People facing homelessness often need to access multiple services to regain stability, such as obtaining an ID or birth certificate, securing free bus tickets, signing up for subsidized housing, or applying for childcare assistance. If they rely on public transportation and have children, it becomes impractical to travel across the city to access these services. As a result, they spend more time navigating the logistics of service access than focusing on finding work or housing. |

Table 6: Early Interventions

| Action | What is it? | Why is it needed? |

| Offer financial training and support | This can encompass opening a bank account, financial management, budgeting, credit improvement, saving, and investing. It also includes broader financial literacy, covering topics such as entrepreneurship, homeownership, and preparation for major life events like college and retirement. | This type of support can empower individuals with the skills to manage their money effectively, build and maintain good credit, and save for emergencies. By understanding financial management, budgeting, and planning for major life events, individuals are better equipped to achieve stability, make informed decisions, and avoid situations that could lead to homelessness. |

| Leverage predictive analytics | These programs aim to identify the most vulnerable individuals before they face eviction. By using data from various sources, such as utility shut-off notices, government benefit applications, or historical records of previous homelessness, algorithms can identify at-risk individuals and offer financial assistance. | Predictive analytics can proactively identify individuals who are at risk of becoming homeless before they reach a crisis point. Through early alerts and targeted assistance, such as financial aid or access to resources, at-risk individuals can stabilize their housing situation and avoid homelessness. |

| Expand supportive housing options | This housing option provides affordable units alongside intensive case management and voluntary support for individuals with behavioral health needs who are leaving incarceration. | Individuals leaving incarceration often face high levels of homelessness because they struggle to qualify for regular housing due to insufficient credit, limited employment history, lack of references, or their criminal record. Supportive housing can enhance housing stability, improve mental and physical health, and prevent substance misuse. |

| Expand treatment access | Access to mental health and substance use treatment could be expanded by training primary care physicians in basic behavioral health care, embedding behavioral health specialists in primary care settings, and increasing funding or incentives to expand local behavioral health services. | Nearly half of Americans who need mental health or substance use treatment do not receive it. Cost and availability continue to be obstacles. Given the link between homelessness and behavioral health disorders, providing accessible treatment options could help prevent loss of housing and serve as an effective intervention. |

| Support clean slate initiatives | Clean slate allows for the automatic expungement or sealing of criminal records for individuals who have completed their sentence and remained law-abiding. | Criminal records can prevent individuals from obtaining employment or housing. For those who have remained crime-free, expunging their record can provide a second chance. |

| Establish third places | This entails providing free public spaces and events where people can gather and build connections outside of their home (first place) or work (second place). This could be a park, community center, or a city-hosted gathering. | These spaces create social cohesion that can provide support networks, reduce isolation, and foster inclusive environments where people are more willing to help those in need. |

| Implement the Critical Time Intervention (CTI) model | Providing time-limited support for vulnerable individuals during transition periods, such as after incarceration or institutionalization. Generally, these programs require small caseloads, provide harm reduction approaches, and are community-based. | Individuals transitioning back into society often lack support systems and struggle to navigate the fragmented support system. Providing support for transitioning individuals can help them reintegrate into the community and ensures continuity of care. CTI has been found to reduce the risk of recurring homelessness. |

Conclusion

Our cities are facing complex crises: a growing chronically homeless population, increasing mental health issues, surging rates of drug overdoses, and overwhelmed jails. Although overall crime rates have been declining, frequent media coverage of crime and social unrest in some areas have heightened feelings of danger among communities. To ensure the health and safety of all community members, including homeless individuals, cities must address these concerns with both immediate and long-term solutions.

Importantly, addressing homelessness requires more than inaction, displacement, or detainment. It requires that stakeholders with different perspectives come together to develop comprehensive, multi-faceted strategies, tailored to specific community needs. A “one-size-fits-all” approach to homelessness is unlikely to succeed. Decision-makers need to recognize the value in diverse strategies and combine them to create more effective solutions. This shift reflects a growing understanding that homelessness is not only a lack of housing; it is a complex issue deeply connected to broader social, economic, and health-related factors. Cities must be bold, innovative, and willing to challenge the status quo to implement effective solutions.

Housing is a critical part of any solution, but different individuals face different challenges, so offering a variety of housing options tailored to individuals’ unique needs will be crucial. Though this approach improves accessibility, providing housing alone is not enough.

Because substance use issues and severe mental health disorders are prevalent among homeless individuals, a range of supportive services is also necessary. Moreover, the co-occurrence of some mental health disorders with drug or alcohol use may increase the likelihood of criminal behavior, making this a particular priority. Addressing this issue generally requires integrated treatment models that combine housing with substance use treatment (e.g., strict sober living environments or a housing-first model that provides a place to live without preconditions and then offers voluntary treatment). For those with behavioral issues that create a significant barrier to maintaining stable shelter, combining housing with mandatory or incentivized treatment might be necessary to ensure long-term success. For those who cannot care for themselves, such as individuals with severe traumatic brain injuries, substance use disorder, or schizophrenia, the focus should be on compassionate intervention that may require some level of involuntary intervention to start.

Police and the courts have long played a role in addressing homelessness, and they will likely continue to do so. However, encampment sweeps and criminal sanctions should always be a last resort. The overuse of police and jails to address homelessness is expensive and often counterproductive. Homeless outreach teams and homeless or community-court models can offer more constructive solutions. If individuals enter the criminal justice system, robust support must be available to prevent a cycle of homelessness and incarceration.

Prioritizing prevention and early intervention through community solutions and public policy may prove most effective in reducing homelessness. Innovative solutions, such as predictive analytics, can play a vital role by identifying those at risk of experiencing homelessness and intervening with support before they become homeless. Additionally, increasing access to other basic needs, like reliable transportation, affordable childcare, and assistance with obtaining government documents and programs, can significantly enhance stability and help prevent homelessness. By appropriately addressing homelessness, we can make our communities feel safer, protect vulnerable individuals, and reduce our overreliance on an expensive carceral system.