How Does the Child Tax Credit Impact Employment? A Simplified Look at Short- and Long-Term Effects

The Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and Child Tax Credit (CTC) have long been celebrated for their ability to reduce child poverty and provide financial stability for families. Recent policy debates have focused on expanding and restructuring the CTC; however, its potential impact on employment continues to shape the conversation. Critics argue that the additional income might discourage work, while supporters contend that the benefits far outweigh any modest reductions in labor supply. To understand these concerns, it is crucial to examine how economists estimate both short- and long-term employment effects.

Tax credits like the EITC and CTC impact labor supply by altering the financial incentives associated with work. These effects primarily operate via the substitution effect, return to work (RTW), and labor supply elasticities.

Key Economic Mechanisms

The substitution effect occurs when tax credits effectively raise after-tax wages, making work more attractive relative to leisure or non-work activities. Abundant evidence shows that EITC expansions in the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s significantly increased employment among unmarried mothers—a group that has long had relatively low labor force participation. There is also evidence that EITC policy changes since the 2000s and CTC expansions since its introduction in 1997 had positive (though relatively small) effects on employment.

RTW quantifies the impact of a tax policy change on work incentives. It is influenced by changes in taxes and tax credits or changes in public assistance for non-workers. When non-workers receive substantial benefits, working becomes less attractive, thereby lowering the RTW. Conversely, programs like the EITC or CTC can increase the RTW by boosting income for those who work, making work more rewarding and encouraging labor force participation.

Labor supply elasticities measure how sensitive individuals’ labor supply decisions are to changes in wages or after-tax income. Labor supply elasticity is the percent change in labor supply divided by the percent change in RTW. For example, a 10 percent increase in the RTW leading to a 3 percent increase in labor supply would imply an elasticity of 0.3. Larger elasticities mean that a given change would lead to a larger change in labor supply.

Tax credits that raise after-tax wages (and the RTW) increase labor supply via the substitution effect. Conversely, removing these credits may reduce labor supply by reducing the RTW.

CTC Policy and Work Incentives

Two policy details should be kept in mind when considering why tax credits like the CTC impact work incentives: the amount of benefits available and how those benefits phase in with earnings. Both steeper phase-in rates and higher benefit levels increase the RTW and lead to higher employment rates via the substitution effect.

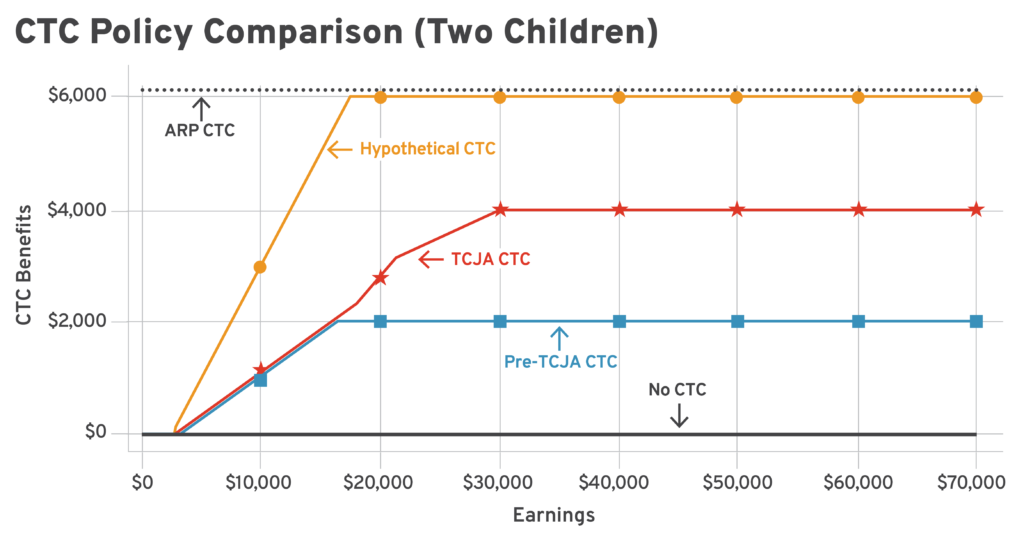

The following graph illustrates these ideas with five different versions of the CTC for a family with two children:

- No CTC at all

- 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) CTC

- Pre-TCJA CTC

- Hypothetical CTC where benefits are larger than the TCJA CTC and phase in quicker

- Temporary 2021 American Rescue Plan (ARP) CTC where full benefits are available to all low-income families, regardless of earnings

Source: R Street analysis of data collected from the National Bureau of Economic Research (TAXSIM)

Consider the impact of replacing the pre-TCJA CTC with the TCJA CTC. While the pre-TCJA CTC increased work incentives relative to no CTC, the TCJA CTC further increased work incentives and the RTW relative to the pre-TCJA CTC for families earning over $16,000 per year. The red and blue lines in the graph show the structure of the pre-TCJA CTC and TCJA CTC, the latter of which expanded the credit from a maximum of $1,000 per child to $2,000 maximum per child.

To understand the impact of this change on work incentives, consider parents with two children debating whether to work. Those who work and earn at least $30,000 per year would receive up to $2,000 in CTC tax credits with the pre-TCJA CTC and up to $4,000 with the TCJA CTC, yielding after-tax earnings of $32,000 and $34,000, respectively. The higher benefits available under the TCJA CTC increased the RTW and likely nudged some parents into the labor force via the substitution effect, though how many depends on their labor supply elasticity. However, because the TCJA CTC did not provide more benefits or phase benefits in faster than the previous CTC, it did not impact income or the RTW for families earning less than $16,000 per year.

Because the hypothetical CTC (the solid green line in the preceding graph) has a steeper phase-in and higher benefits than the TCJA CTC, the policy would increase income and the RTW even more than the TCJA CTC. A CTC policy designed to increase the benefits and work incentives available to lower- income working families might resemble this hypothetical CTC.

Not all CTC expansions would increase labor supply, however; it depends on whether benefits phase in with earnings. Consider the ARP CTC (the dashed green line in the preceding graph) where full benefits are available to the poorest families—even those without any earnings. While this type of CTC would ensure benefits go to the poorest families, it would also reduce the RTW relative to a CTC that phases in with earnings. The exact size of the RTW reduction depends on which CTC policy details are replaced. Implementing the ARP CTC by replacing (and eliminating) the hypothetical CTC in the graph would lead to a sizable reduction in the RTW, replacing the TCJA CTC would lead to a smaller RTW reduction, and replacing the pre-TCJA CTC would lead to an even smaller reduction.

Debates over the impact of the ARP CTC on work incentives were largely about how much eliminating the TCJA CTC would impact work incentives. Note that if the ARP CTC were implemented in a context of no CTC (or if it left the existing CTC in place and built upon it), the policy would not affect work incentives via the substitution effect. This scenario describes Canada’s expansion of universal child allowances in 2015 and 2016 and helps explain why this policy had no effect on parental employment. It is worth noting that CTC policies could also theoretically impact work incentives via the smaller and less significant income effect channel.

Moving from the theoretical to the empirical, several studies have examined the labor-supply effects of replacing the TCJA CTC with the temporary 2021 ARP CTC. Two research papers found precise null effects, a third found a statistically insignificant negative effect that implied a total disemployment effect of 344,000 to 495,000 working parents, and a fourth found evidence suggesting a decline in employment among single mothers. Each of these studies estimated effects by comparing families with and without children and examining employment trends in the months before and after the expanded 2021 CTC expired. However, because the CTC was temporary (and responses to policies often take a few years to fully manifest), these studies may underestimate the potential longer-term impact on labor supply if the ARP CTC were to permanently replace the TCJA CTC.

The best way to forecast the longer-term impact of a CTC policy change on labor supply is to carry out a simulation by modeling changes in the RTW, applying elasticity assumptions by gender and marital status, and projecting overall employment changes. A handful of researchers have done this, predicting total employment effects (number of parents leaving the workforce) ranging from 300,000 to 1,460,000, with most estimates falling between 300,000 and 400,000. The main reason for this wide range is the variation in labor supply elasticities used. Economists who apply different elasticities generally arrive at considerably different conclusions. Which elasticity magnitudes are considered reasonable is hotly debated, especially given that a wide range of elasticities have been found over the last few decades. Determining the “correct” elasticity is crucial to understanding the potential effects of a particular policy choice.

As if female labor supply elasticities were not complicated enough, strong evidence suggests they have shrunk over time. More women have shifted from being secondary earners to primary earners. This pattern of declining elasticities has become apparent in the United States and in several other countries over the last few decades. The trend is evident for both married and unmarried women, with and without children. Combined with broader societal changes like increased labor force participation and evolving gender roles, this shift suggests that today’s policy changes—such as adjustments to the CTC—would likely have a smaller impact on the female labor supply than similar policies implemented in earlier decades.

Conclusion

Understanding the employment effects of the CTC requires a careful consideration of substitution effects, the RTW, and labor supply elasticities. These concepts provide critical insights into how CTC policies shape work incentives. The key to assessing the impact of a new CTC lies in determining which existing policy it would replace. A new CTC that phases in with earnings and offers higher benefits would generally increase the RTW, but the magnitude of its effects depends on the baseline policy. For example, replacing the TCJA CTC with a new design would have a relatively larger impact on work incentives compared to replacing the pre-TCJA CTC, which Congress has scheduled to reinstate after 2025 unless TCJA provisions are extended. As lawmakers debate the future of the CTC, understanding these dynamics is crucial to balancing the goals of supporting families and maintaining labor force participation.