Emission Benefits of Permitting Reform

Authors

Table of Contents

- Executive Summary

- Introduction

- Policy Discourse on Permitting Reform

- Why Emission Savings Matter in the Permitting Reform Debate

- Measuring Possible Emission Savings Through Permitting Reform

- Policy Insights and Recommendations

- Conclusion

Media Contact

For general and media inquiries and to book our experts, please contact: pr@rstreet.org

Policies that improve permitting timelines in the United States make sense both economically and environmentally and must be considered moving forward.

Executive Summary

In recent years, policymakers have spotlighted permitting reform, incorporating it into 2023’s Fiscal Responsibility Act and introducing related legislation in 2024.[1] The issue has been gaining traction because governmental entities have been taking increasingly longer to issue permits.[2] This alone is relevant to energy projects and supporting infrastructure that require permits, but, even beyond this, there has also been an increase in energy-specific ordinances that restrict permitting.[3] From an energy and economics standpoint, protracted permitting timelines impede the market entry of new resources and thus delay the economic benefits of newer, more efficient resources.

A key challenge in implementing permitting reform is the potential environmental impacts, as much of permitting is focused on environmental protection. Although permitting reform could improve efficiency in deploying new energy production, that potential expediency of energy permitting would also extend to fossil fuels. As such, opposition to permitting reform is often predicated on environmental claims, especially a climate-change argument that—even though permitting reform would benefit both clean energy and fossil fuels—the emission increases of fossil resources would outweigh the avoided emissions from clean energy deployment.[4]

Importantly, though, considerable research has found that clean energy is more likely to require comprehensive permitting, that the transmission lines necessary for clean energy growth take longer to permit, and that the emission abatement potential of climate policies depends on faster permitting of clean energy projects and associated grid infrastructure.[5] These findings led us to question whether permitting reform, rather than having negative consequences for the environment and climate change in particular, could instead have a positive environmental effect.

In this paper, we seek to answer that question with quantifiable data by estimating the potential magnitude of emission abatement that might come from permitting reform. We accomplish this by comparing projections of future clean energy deployment and estimating the potential emission benefits of shifting their market entry forward via shorter permitting timeframes. We estimated this using two different assumptions. First, we assumed that the historical average of 36 months for new resources to begin commercial operation applies today. Second, we looked at how the abatement estimate would change if the average permitting timeframes were closer to 60 months, as newer data suggests.

Conservatively assuming 36-month permitting averages, we found that improving permitting timelines by up to 25 percent could reduce U.S. electric power sector CO2 emissions by up to 452 million metric tons over a 10-year period, or about 4.7 percent of U.S. electric power emissions (1 percent of overall U.S. energy-related CO2 emissions for all sectors and sources). Assuming that current permitting timelines are closer to 60 months and that they could be brought down to an aspirational target of 24 months, the potential emission abatement would increase to at least 1.3 billion metric tons, or about 13 percent of U.S. electric power emissions (3 percent of overall U.S. energy-related CO2 emissions for all sectors and sources).

These findings indicate that permitting reform has the potential to offer significant reductions in U.S. greenhouse gas emissions, in addition to the expected economic benefits. While this analysis does not utilize these findings to leverage specific new policy recommendations, past R Street policy recommendations are still relevant to permitting reform:

1. New restrictions on energy deployment should focus on alleviating the harms caused by new infrastructure rather than on pursuing moratoria or technology-specific restrictions.[6]

2. The federal government should adopt policies that reduce the time it takes to issue federal permits—such as modifying how the federal government manages judicial review—to ensure that permitting agencies receive the information they need as early as possible.[7]

3. Alternative climate policies that incur substantial costs, such as regulation or subsidies, should not be prioritized over permitting reform, as such policies are unlikely to yield their claimed benefits in the absence of permitting reform.[8]

Overall, we conclude that permitting reform has significant potential to offer climate benefits from the earlier market entry of clean energy and its supporting infrastructure. We find that the key argument against permitting reform—that more efficient permitting would increase fossil fuel use and raise emissions post-reform—is unlikely to be true.

Introduction

One of the central questions in U.S. climate policy is the extent to which clean energy will replace fossil fuels. Proponents of major climate-related policies, such as the energy subsidies from the Inflation Reduction Act, believe that these policies will facilitate the replacement of fossil fuels with clean energy.[9] Although R Street often disputes the merits of subsidies as a climate policy, a more fundamental question is at play: Can clean energy be permitted and constructed quickly enough to attain the hoped-for greenhouse gas (GHG) emission curtailment?[10]

While analyses of the benefits of clean energy often assume that there are no barriers to the market entry and operation of such sources, this is not the case. Clean energy is not only more likely to require complex permitting processes, but such projects also face ever-increasing permitting restrictions.[11] As a result, broad support for the idea of “permitting reform” is growing not just as a matter of economic policy but as one of environmental concern as well. Moreover, although some policymakers have historically viewed complex and difficult permitting as environmental protection, there is now concern that the very processes intended to protect the environment may, in fact, shield incumbent fossil fuels from the competition of clean energy.[12]

Permitting reform for all infrastructure (not just clean energy) is an ongoing policy issue that has only been addressed incrementally thus far. In 2015, the Fixing America’s Surface Transportation Act included accelerated processes for permitting large energy and transportation-related projects.[13] In 2023, Congress passed legislation intended to address permitting delays by narrowing the scope of projects requiring federal permits and easing project review.[14] And in 2024, substantial legislation that would have further modified federal permitting by limiting the opportunity for states to delay transmission permits and shortening the statute of limitations was nearly adopted.[15] Most recently, the Trump administration has also directed federal agencies to accelerate permitting.[16]

If policymakers expedited permitting, most new construction projects for energy-related infrastructure would be related to clean energy.[17] As such, permitting reform not only has the potential to increase energy supply but also to deliver the added benefit of reducing GHG emissions.[18]

This paper describes the current landscape of permitting reform and quantitatively assesses the potential emission abatement that permitting reform could deliver to demonstrate how such efforts might compare with other climate policies, such as subsidies or regulation. With that in mind, we estimate the potential CO2 emission abatement that permitting reform could offer within a 10-year window and explore the relevance of those potential savings on permitting reform discourse. Finally, we offer specific recommendations that policymakers can consider to support reasonable reform and recognize the identified savings.

Policy Discourse on Permitting Reform

Permitting reform has become an increasingly important, increasingly debated issue among policymakers. Those who support reforms point to a growing body of research demonstrating that permitting delays are impeding advances in the energy sector.[19] For example, a recent survey of energy investors found permitting issues to be the most significant factor in determining whether wind and solar projects were canceled.[20] In addition, many energy companies signed onto a letter urging Congress to advance additional permitting reform, noting that such reforms could have both economic and environmental benefits.[21] Those who oppose permitting reform believe that such efforts would advance fossil fuel and mineral extraction in the United States, with negative consequences to the environment and climate.[22] Given that the crux of this debate often focuses on beliefs and assumptions about the environmental and climate impacts of permitting reform, leveraging existing data to estimate the potential emission outcomes of reforms, as we do in this paper, is especially relevant to current discussions.

Importantly, policymakers who believe that permitting delays are impeding energy-sector advances generally point to three specific contributing issues: the increasing length of time needed to secure permits, the growing number of restrictions related to deploying new projects, and the disproportionate way these increasing timelines and restrictions negatively affect clean energy projects.

First, the time it takes for energy projects to complete the permitting process is increasing. R Street research conducted in 2021 confirmed that this is true of federal permits, with the average time to complete the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) process increasing from 3.4 years in 2010 to 4.7 years in 2019.[23] Similarly, a 2024 report from Lawrence Berkeley National Lab found that the time for new power plants to be approved for commercial operation was increasing, approaching an average of 4 to 5 years.[24]

Second, there are currently more restrictions for deploying energy-related infrastructure projects than there were in the past. Previous R Street research found that at least 13 percent of counties in the United States have ordinances that restrict the deployment of wind power, and 9 percent have ordinances restricting solar.[25] Moreover, the rate at which these new local ordinances are being adopted is increasing; for wind power, for example, the number of new ordinances imposed each year increased 16-fold from 2003 to 2023.[26]

Third, clean energy projects are uniquely affected by permitting delays and restrictions. Although opposition to permitting reform typically comes from conservation groups that are ostensibly pro-clean energy, previous R Street research has consistently shown that clean energy is more likely to encounter permitting difficulties than fossil fuels.[27] Additionally, another group’s research supports this idea, as they found that permitting for electric transmission lines (which are needed for clean energy growth) takes longer than permitting for natural gas pipelines, suggesting that permitting improvements would likely benefit clean energy more than fossil fuels.[28] Of note, protracted permitting timelines not only stall pro-environment projects but also stymie the emission benefits projected to result from certain Inflation Reduction Act measures; over 80 percent of the potential emission benefits expected from the Act’s subsidies are contingent upon a more permissive permitting environment for electric power transmission.[29]

Why Emission Savings Matter in the Permitting Reform Debate

The permitting reform debate largely centers around environmental impact. Although the potential economic benefits of permitting reform are clear, and industry would always advocate for less red tape, the argument against reform hinges on the claim that the potential environmental harms outweigh the potential economic benefits. Importantly, climate change is a primary environmental concern, and those against permitting reform believe that additional fossil fuel infrastructure would be deployed if permitting reforms were implemented.

With these concerns in mind, estimating the emission benefits of permitting reform can help policymakers find a path forward. If permitting reform is shown to have only a slight emission benefit, then the argument for reform would have to rely on potential economic benefits outweighing potential environmental harms. However, if the potential emission benefits are substantial, opponents’ concern that permitting reform would advance fossil fuels would carry notably less weight, as such reforms would be climate-improving rather than climate-damaging. Under the latter scenario, the case for permitting reform would be supported on both economic and climate-related grounds, rather than simply economics.

Measuring Possible Emission Savings Through Permitting Reform

Assumptions and Methodology

In our research, we sought to estimate the magnitude of CO2 emission abatement that could be attained via permitting reform. To do so, we assessed estimates of nine different permitting timelines based on historical averages and current permitting timeframes for new electric power–generating resources to begin commercial operation and forecasted how much more capacity could be added to the electric power grid assuming shorter permitting timelines for the market entry of resources. We then estimated the potential amount of avoided CO2 from 2024 to 2033, assuming an earlier market entry of clean energy resources.

Our calculations assumed that 1 gigawatt (GW) of installed capacity corresponds to a certain amount of electricity generation annually based on the capacity factor of each technology. Solar energy has an estimated capacity factor of around 30 percent, resulting in approximately 2,628,000 megawatt-hours (MWh), or 2.628 terawatt-hours (TWh), generation per GW installed capacity annually. Wind energy has an estimated capacity factor of about 45 percent and 3,942,000 MWh, or 3.942 TWh, generation per GW installed capacity.

We considered different scenarios to represent varying levels of permitting acceleration for faster renewable energy deployment. Baseline and timeframe reductions of 15 percent, 20 percent, and 25 percent were estimated for the assumption of a 36-month current average permitting timeframe. Similarly, baseline and timeframe reductions of 15 percent, 20 percent, 25 percent, 40 percent, and 60 percent were estimated for the assumption of a 60-month current average permitting timeframe. Baseline capacity additions for 2024 to 2033 total 3,840 GW (according to the Energy Information Administration), with scenario-based variations adjusting this figure upward with shorter timelines (Appendix A and B).

Our calculations of avoided emissions were based on displaced fossil fuel generation (coal and gas). We used emission intensity factors from the Environmental Protection Agency for coal and gas plants to determine the avoided emissions per GW of generation and assumed that the CO2 reductions per unit of energy replaced by renewables and resulting from permitting reforms would enhance renewable deployment (Appendix C and D).

We identified the share of coal and gas in the displaced generation mix and calculated potential avoided CO2 emissions separately for coal and gas scenarios. Standard emission rates (metric tons CO2 per MWh) for coal and gas were used, and total avoided CO2 was determined by multiplying displaced MWh by total installed capacity, first for baseline and then for respective total installed capacity with permitting timeframe reductions. Faster deployment scenarios assumed increased permitting efficiency, leading to higher potential avoided emissions.

Findings

Our research shows that even modest improvements in permitting timelines would yield substantial emission abatement—likely hundreds of millions of metric tons of avoided CO2 from the electric power sector over a 10-year period.

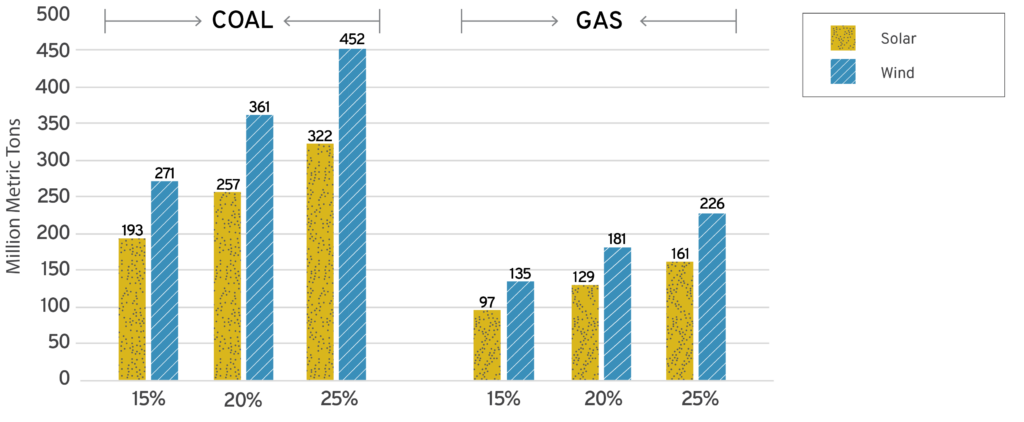

Figure 1 shows the emission abatement potential, assuming current permitting timelines averaging 3 years and permitting reform delivering up to 25 percent faster permitting (see also Appendix C).

Figure 1: Potential CO2 Avoided Assuming a Current Permitting Average of 36 Months

Assuming that current permitting times average 36 months and that those times could be decreased by 15 to 25 percent, we calculated that improved permitting timeframes would avoid between 193 and 322 million metric tons of CO2 for solar replacing coal and between 271 and 452 million metric tons for wind replacing coal. For replacing natural gas, we found a potential avoided CO2 of 97 to 161 million metric tons using solar and 135 to 226 million metric tons using wind. Overall, this would reduce power-sector CO2 emissions by up to 4.7 percent, or overall U.S. energy-related CO2 emissions by 1.1 percent.

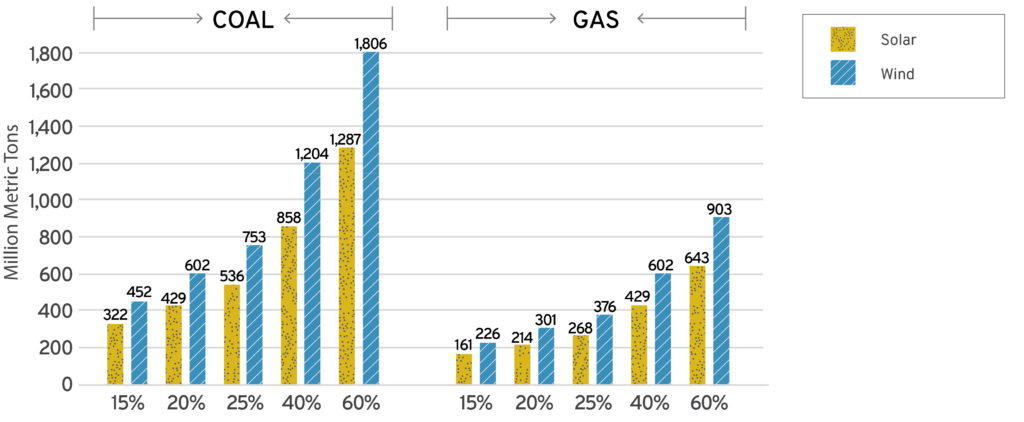

Importantly, Figure 1 assumes a current industry average of 36 months before new projects can begin commercial sales of electricity, which is the average of the past decade.[30] But those timelines are increasing, and recent industry norms may be longer—closer to 60 months.[31] This potentially longer average timeframe would also be consistent with estimates of current federal permitting timeframes, which are 4.5 years for energy projects and 6.5 years for transmission projects.[32] Essentially, regardless of which assumption one uses for baseline permitting timelines, multiple data sources and permitting processes indicate that a longer, 5-year permitting timeline is becoming the norm. Figure 2 demonstrates the impact of revising our assumption for current permitting timelines from 36 months to 60 months and correspondingly revising the permitting timeline reduction to up to 60 percent faster (i.e., by moving from 5-year permitting timeframes to 2-year permitting timeframes; see also, Appendix D).

Figure 2: Potential CO2 Avoided Assuming a Current Permitting Average of 60 Months

If current permitting timelines are, in fact, averaging closer to 60 months, then accelerating permits by 15 to 25 percent would yield an emission benefit between 322 and 536 million metric tons for solar and 452 and 753 million metric tons for wind for replacing coal. Furthermore, based on this 60-month average, a 60 percent improvement in timeline (i.e., going from 5 years to 2 years) would avoid up to 1,287 million metric tons of CO2 emissions for solar and 1,806 million metric tons for wind. Overall, this would reduce total electric power CO2 emissions by up to 18.7 percent or overall U.S. energy-related CO2 emissions for all sectors and sources by 4.3 percent.

However, readers should note that various factors could substantially alter our estimates in either a positive or negative way. For example, we did not include the benefits of faster permitting for transmission infrastructure, which could improve the capacity factor of clean energy resources and thus the emission benefits. We also assumed that new generating resources would displace incumbent fossil fuel generation, but new deployment could also displace aged clean energy resources.

It is also important to note that we assessed these policies across a 10-year timeframe because that timeframe is the industry standard for policy analysis, but accelerating emission abatement results in a compounding climate benefit in the years beyond our analysis window. That is, the emissions avoided from the earlier market entry of clean energy do not end after 10 years, and comparisons of the emission benefits of permitting reform to other policies should utilize consistent timeframes.

Discussion of Findings

A key measure of the success of any implemented policy is whether its benefits outweigh its costs. This is particularly relevant for environmental issues, where most policies incur economic costs with the expectation that the environmental benefit will outweigh the investment. Permitting reform is somewhat different in that it is expected to carry an economic benefit by reducing artificial barriers to the market entry of new infrastructure. The argument opposing permitting reform largely hinges on the idea that the environmental harms of new infrastructure outweigh the economic benefits, but, as noted above, substantial evidence demonstrates that clean energy—and thus the environment—is more likely to benefit from permitting reform.

Although past analyses, including those from R Street, have shown that permitting reform is important for advancing clean energy, they have not examined how permitting reform might affect emission abatement.[33] Our findings indicate that permitting reform should be recognized as a significant pathway to emission abatement, potentially abating up to 18.7 percent of electric power sector CO2 emissions. Importantly, our findings also indicate that longer permitting timelines carry an environmental cost from increased power sector emissions.

Considering that permitting reform would be both economically and environmentally beneficial, the environmental case against it notably weakens. Additionally, these synergistic benefits reinforce past research that has shown that the environmental effectiveness of other policies, such as clean energy subsidies, also depends on accompanying permitting reform.[34] Ultimately, we find it extremely unlikely that any corresponding increases in fossil fuel infrastructure resulting from permitting reform would yield an emission increase that would outweigh the emission abatement from accelerated clean energy infrastructure. Although the degree of emission benefit from permitting reform largely depends on the degree to which the permitting process could be shortened, permitting reform must be considered a significant policy for abating U.S. GHG emissions.

Policy Insights and Recommendations

Because permitting reform would accelerate the deployment of private capital into the market, it would not involve a conventional cost borne by the public, like a subsidy would. On the contrary, permitting reform carries a benefit to the public, as it enables lower-cost resources to displace higher-cost incumbent ones, while simultaneously improving the relative carbon intensity of energy production. This means that independent of the degree to which permitting reform abates emissions, it is still an economically beneficial policy.

The potential climate benefits of permitting reform are largely contingent on the anticipated deployment of future clean energy resources. An analysis of recent grid interconnection queues highlights that electric-generating resources seeking grid interconnection are predominantly clean-energy related, which suggests that the climate benefits of permitting reform are high and increasing.[35] Additionally, as noted earlier, evidence suggests that permitting is becoming increasingly difficult, meaning that the potential emission benefits of permitting reform are likely to grow over time.

From a policy perspective, these findings further demonstrate that permitting reform can create environmental and climate benefits in addition to economic benefits—a concept that past R Street research has also supported.[36] Thus, broadly, we recommend that:

1. States and localities improve their processes for approving energy resources while minimizing the adoption of restrictive ordinances that may not carry much benefit. R Street has previously suggested that this could be attained by tying restrictive ordinances to the harms that they hope to avoid, rather than targeting specific energy production (e.g., wind ordinances should be focused on mitigating noise rather than establishing moratoria on new construction).[37]

2. The federal government address deficiencies in its permitting processes, especially as it pertains to increasingly time-consuming compliance with NEPA and litigation risk. Policy reforms, such as addressing judicial review, would accelerate the timelines of federal permitting.[38]

3. Climate policy prioritize permitting over alternative policies such as subsidies or regulation.[39] Because the ability to avoid GHG emissions largely depends on new capital entering the market, policies that are mostly focused on alleviating capital availability, or prohibiting emitting activities, are not as effective because they still require the deployment of new permitted energy-related infrastructure to be effective.

Conclusion

Although permitting reform has always been relevant to climate policy because it affects the mix of future energy entering the market, until now, much of the emission-based debate for or against permitting reform has relied on economic theory or indirect variables. As such, we believe there is substantial value in identifying the magnitude of emission abatement that permitting reform could deliver by accelerating the deployment of clean energy.

Our analysis finds that the potential emission abatement effects that could be achieved through permitting reform are contingent on the degree of present-day delays for permits, the effectiveness of reform in accelerating permits, and the level of substitution that new resources have with incumbent generation sources. Overall, based on present-day data, we estimate that permitting reform could avoid between 97 and 452 million metric tons of CO2, assuming reported industry averages. We also calculate that if our assumptions are too conservative and the commonly reported average of 5 years to permit facilities is more accurate, this value could increase to 643 to 1,806 million metric tons if permitting timelines were shortened to 2 years. This level of abatement would reduce total U.S. electric power emissions by up to 18.7 percent and overall U.S. energy-related CO2 emissions for all sectors and sources by 4.3 percent.

Ultimately, our findings substantially weaken arguments against permitting reform that theorize that such policy changes would increase emissions or fossil fuel reliance. In fact, a pro-climate argument is one in favor of permitting reform rather than against it, given the significant emission benefits that could be unlocked from faster permitting. Policies that improve permitting timelines in the United States make sense both economically and environmentally and must be considered moving forward.

Appendix A

Additional Estimated Capacity from Faster Permitting Assuming a Current Permitting Average of 36 Months

| Technology | Baseline Additions (2024–2033) (GW) | 15% Faster Timeline (GW) | 20% Faster Timeline (GW) | 25% Faster Timeline (GW) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solar | 3,840 | 3,912 | 3,936 | 3,960 |

| Wind | 2,507 | 2,574 | 2,597 | 2,619 |

Appendix B

Additional Estimated Capacity from Faster Permitting Assuming a Current Permitting Average of 60 Months

| Technology | Baseline Additions (2024–2033) (GW) | 15% Faster Timeline (GW) | 20% Faster Timeline (GW) | 25% Faster Timeline (GW) | 40% Faster Timeline (GW) | 60% Faster Timeline (GW) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solar | 3,840 | 3,960 | 3,936 | 4,040 | 4,160 | 4,320 |

| Wind | 2,507 | 2,619 | 2,597 | 2,694 | 2,807 | 2,956 |

Appendix C

Potential CO2 Avoided Assuming a Current Permitting Average of 36 Months

| Technology | CO₂ Avoided for Replacing Coal – Million Metric Tons by % Faster Timelines | CO₂ Avoided for Replacing Gas – Million Metric Tons by % Faster Timelines | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15% | 20% | 25% | 15% | 20% | 25% | |

| Solar | 193 | 257 | 322 | 97 | 129 | 161 |

| Wind | 271 | 361 | 452 | 135 | 181 | 226 |

Appendix D

Potential CO2 Avoided Assuming a Current Permitting Average of 60 Months

| Technology | CO2 Avoided for Replacing Coal – Million Metric Tons by % Faster Timelines | CO2 Avoided for Replacing Gas – Million Metric Tons by % Faster Timelines | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15% | 20% | 25% | 40% | 60% | 15% | 20% | 25% | 40% | 60% | |

| Solar | 322 | 429 | 536 | 858 | 1,287 | 161 | 214 | 268 | 429 | 643 |

| Wind | 452 | 602 | 753 | 1,204 | 1,806 | 119 | 194 | 269 | 495 | 903 |

[1]. H.R. 3746, Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023, 118th Congress. https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/house-bill/3746; S.4753, Energy Permitting Reform Act of 2024, 118th Congress. https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/senate-bill/4753.

[2]. “U.S. Permitting Delays Hold Back Economy, Cost Jobs,” American Clean Power, April 2024. https://cleanpower.org/wp-content/uploads/gateway/2024/04/ACP-Pass-Permitting-Reform_Fact-Sheet.pdf.

[3]. Devin Hartman et al., “State and Local Permitting for the Energy Sector: Challenges and Opportunities,” R Street Policy Study No. 313, November 2024, p. 8. https://www.rstreet.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/FINAL-R-street-policy-study-no-313.pdf.

[4]. “Energy Permitting Reform Act of 2024 Opposition sign-on letter,” Friends of the Earth, November 2024. https://foe.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/Letter-Opposing-Energy-Permitting-Reform-Act-of-2024.pdf.

[5]. Philip Rossetti, “Current Share of Energy Projects Requiring High-Level Review that Are Clean Energy,” R Street Institute, Aug. 17, 2023. https://www.rstreet.org/commentary/current-share-of-energy-projects-requiring-high-level-review-that-are-clean-energy; Rayan Sud et al., “How to Reform Federal Permitting to Accelerate Clean Energy Infrastructure: A Nonpartisan Way Forward,” Brookings, February 2023, p. 9. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/20230213_CRM_Patnaik_Permitting_FINAL.pdf; Jesse D. Jenkins et al., “Electricity Transmission is Key to Unlock the Full Potential of the Inflation Reduction Act,” Princeton University Zero Lab, September 2022, p. 4. https://repeatproject.org/docs/REPEAT_IRA_Transmission_2022-09-22.pdf.

[6]. Hartman et al., p. 8. https://www.rstreet.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/FINAL-R-street-policy-study-no-313.pdf.

[7]. Philip Rossetti, “Day One Project: Improving Environmental Outcomes from Infrastructure by Addressing Permitting Delays,” Federation of American Scientists, October 2021. https://fas.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/NEPARossetti.pdf.

[8]. Testimony of Philip Rossetti, Select Committee on the Climate Crisis, United States House of Representatives, “Hearing On: A Big Climate Deal: Lowering Costs, Creating Jobs, and Reducing Pollution with the Inflation Reduction Act,” Sept. 29, 2022, pp. 5-6. https://www.congress.gov/117/meeting/house/115170/witnesses/HHRG-117-CN00-Wstate-RossettiP-20220929-U1.pdf.

[9]. John Larsen et al., “A Turning Point for US Climate Progress: Assessing the Climate and Clean Energy Provisions in the Inflation Reduction Act,” Rhodium Group, Aug. 12, 2022. https://rhg.com/research/climate-clean-energy-inflation-reduction-act.

[10]. Philip Rossetti, “Low-Energy Fridays: Are all these energy subsidies worth it? Not really,” R Street Institute, Nov. 15, 2024. https://www.rstreet.org/commentary/low-energy-fridays-are-all-these-energy-subsidies-worth-it-not-really.

[11]. Philip Rossetti, “The Environmental Case for Improving NEPA,” R Street Institute, July 7, 2021. https://www.rstreet.org/commentary/the-environmental-case-for-improving-nepa.

[12]. Ibid.

[13]. “FAST-41 Program,” Federal Permitting Improvement Steering Council, Dec. 11, 2024. https://www.permitting.gov/projects/title-41-fixing-americas-surface-transportation-act-fast-41.

[14]. H.R. 3746, Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023, 118th Congress. https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/house-bill/3746.

[15]. Philip Rossetti, “Manchin and Barrasso Revive Permitting Reform This Congress,” R Street Institute, July 30, 2024. https://www.rstreet.org/commentary/manchin-and-barrasso-revive-permitting-reform-this-congress.

[16]. “Unleashing American Energy,” The White House, Jan. 20, 2025. https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/01/unleashing-american-energy.

[17]. Philip Rossetti, “Current Share of Energy Projects Requiring High-Level Review that Are Clean Energy.” https://www.rstreet.org/commentary/current-share-of-energy-projects-requiring-high-level-review-that-are-clean-energy.

[18]. Heather Reams, “Permitting reform will help lower emissions,” Washington Examiner, Sept. 16, 2024. https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/opinion/3153629/permitting-reform-lower-emissions-nepa; Conrad La Joie, “Why the Energy Permitting Reform Act is a necessary step forward,” Niskanen Center, Oct. 22, 2024. https://www.niskanencenter.org/why-the-energy-permitting-reform-act-is-a-necessary-step-forward; Xan Fishman et al., “Finding the Goldilocks Zone for Permitting Reform,” Bipartisan Policy Center, Jan. 31, 2024. https://bipartisanpolicy.org/report/golidlocks-zone-bipartisan-permitting-reform-deal.

[19]. Lauren Bauer et al., “Eight facts about permitting and the clean energy transition,” Brookings, May 22, 2024. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/eight-facts-about-permitting-and-the-clean-energy-transition; John Jacobs, “Permitting Speeds Up, but 61% of Reviews Are Still Late,” Bipartisan Policy Center, Jan. 28, 2025. https://bipartisanpolicy.org/blog/permitting-speeds-up-but-61-of-reviews-are-still-late; Council on Environmental Quality, “Length of Environmental Impact Statements (2013-2018),” Executive Office of the President, June 12, 2020. https://ceq.doe.gov/docs/nepa-practice/CEQ_EIS_Length_Report_2020-6-12.pdf; “Study: The Impact of Federal Permitting Delays on Pennsylvania’s Energy Supply Chain,” Americans for Prosperity, 2023. https://americansforprosperity.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/AFP-PA-ARBO-Report-FINAL.pdf; Nikki Chiappa et al., “Understanding NEPA Litigation: A Systematic Review of Recent NEPA-Related Appellate Court Cases,” The Breakthrough Institute, last accessed April 2, 2025. https://thebreakthrough.imgix.net/Understanding-NEPA-Litigation_v4.pdf.

[20]. Bauer et al. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/eight-facts-about-permitting-and-the-clean-energy-transition.

[21]. “Letter to Congress on Company-Identified Permitting Reform Priorities,” Center for Climate and Energy Solutions, July 27, 2023. https://www.c2es.org/press-release/letter-to-congress-on-company-identified-permitting-reform-priorities.

[22]. “Energy Permitting Reform Act of 2024 Opposition sign-on letter.” https://foe.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/Letter-Opposing-Energy-Permitting-Reform-Act-of-2024.pdf.

[23]. Philip Rossetti, “Addressing NEPA-Related Infrastructure Delays,” R Street Policy Study No. 234, July 2021, p. 5. https://www.rstreet.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/FINAL_RSTREET234.pdf.

[24]. Joseph Rand et al., “Queued Up: 2024 Edition,” Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, April 2024, p. 41. https://emp.lbl.gov/sites/default/files/2024-04/Queued Up 2024 Edition_R2.pdf.

[25]. Philip Rossetti and Josiah Neeley, “State and Local Permitting Restrictions on Wind Energy Development,” R Street Institute, July 10, 2024. https://www.rstreet.org/commentary/state-and-local-permitting-restrictions-on-wind-energy-development; Philip Rossetti and Josiah Neeley, “State and Local Permitting Restrictions on Solar Energy Development,” R Street Institute, July 10, 2024. https://www.rstreet.org/commentary/state-and-local-permitting-restrictions-on-solar-energy-development.

[26]. Devin Hartman et al., “State Energy Infrastructure Permitting and Siting Series: Conclusion,” R Street Institute, Aug. 15, 2024. https://www.rstreet.org/commentary/state-energy-infrastructure-permitting-and-siting-series-conclusion.

[27]. Rossetti, “Addressing NEPA-Related Infrastructure Delays,” p. 7. https://www.rstreet.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/FINAL_RSTREET234.pdf; Rossetti, “The Environmental Case for Improving NEPA.” https://www.rstreet.org/commentary/the-environmental-case-for-improving-nepa.

[28]. Sud et al. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/20230213_CRM_Patnaik_Permitting_FINAL.pdf.

[29]. Jenkins et al., p. 4. https://repeatproject.org/docs/REPEAT_IRA_Transmission_2022-09-22.pdf.

[30]. Rand et al., p. 41. https://emp.lbl.gov/sites/default/files/2024-04/Queued Up 2024 Edition_R2.pdf.

[31]. Ibid.

[32]. “U.S. Permitting Delays Hold Back Economy, Cost Jobs.” https://cleanpower.org/wp-content/uploads/gateway/2024/04/ACP-Pass-Permitting-Reform_Fact-Sheet.pdf.

[33]. Rossetti and Neeley, “State and Local Permitting Restrictions on Wind Energy Development.” https://www.rstreet.org/commentary/state-and-local-permitting-restrictions-on-wind-energy-development; Rossetti and Neeley, “State and Local Permitting Restrictions on Solar Energy Development.” https://www.rstreet.org/commentary/state-and-local-permitting-restrictions-on-solar-energy-development; Hartman et al., “State Energy Infrastructure Permitting and Siting Series: Conclusion.” https://www.rstreet.org/commentary/state-energy-infrastructure-permitting-and-siting-series-conclusion.

[34]. Jenkins et al., p. 4. https://repeatproject.org/docs/REPEAT_IRA_Transmission_2022-09-22.pdf.

[35]. Rand et al., p. 11. https://emp.lbl.gov/sites/default/files/2024-04/Queued Up 2024 Edition_R2.pdf.

[36]. Rossetti and Neeley, “State and Local Permitting Restrictions on Wind Energy Development.” https://www.rstreet.org/commentary/state-and-local-permitting-restrictions-on-wind-energy-development; Rossetti and Neeley, “State and Local Permitting Restrictions on Solar Energy Development.” https://www.rstreet.org/commentary/state-and-local-permitting-restrictions-on-solar-energy-development; Hartman et al., “State Energy Infrastructure Permitting and Siting Series: Conclusion.” https://www.rstreet.org/commentary/state-energy-infrastructure-permitting-and-siting-series-conclusion.

[37]. Hartman et al., “State and Local Permitting for the Energy Sector: Challenges and Opportunities,” p. 8. https://www.rstreet.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/FINAL-R-street-policy-study-no-313.pdf.

[38]. Rossetti, “Day One Project: Improving Environmental Outcomes from Infrastructure by Addressing Permitting Delays.” https://fas.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/NEPARossetti.pdf.

[39]. Testimony of Philip Rossetti, pp. 5-6. https://www.congress.gov/117/meeting/house/115170/witnesses/HHRG-117-CN00-Wstate-RossettiP-20220929-U1.pdf.