International Emissions Trends, and How This Should Inform U.S. Climate Policy

Introduction

As a new administration takes the reins on what role climate change may play in U.S. foreign policy, it is worth better examining the current and projected global CO2 emissions, which account for most greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

Global CO2 emissions are rising, but there’s nuance

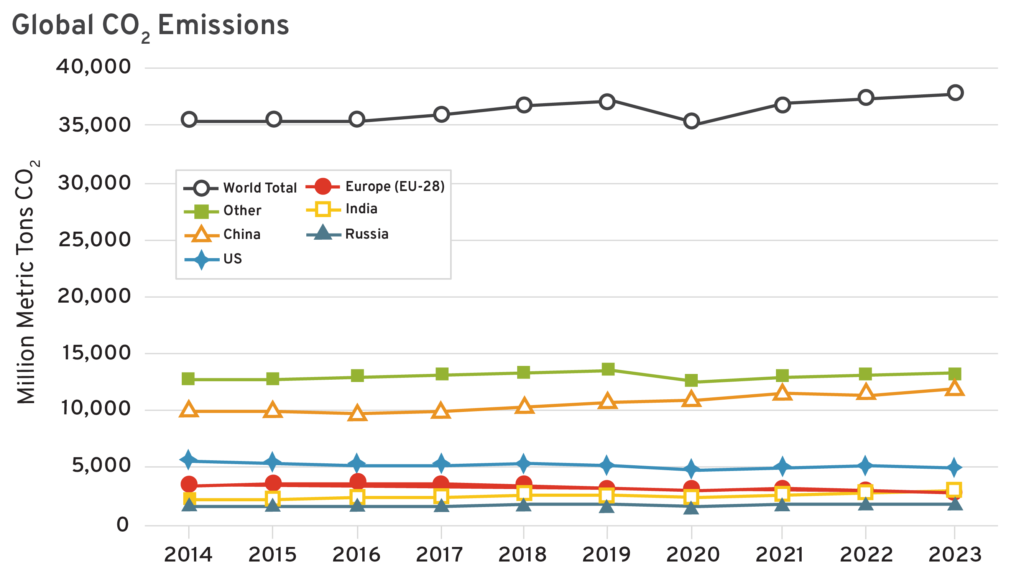

Overall CO2 emissions are increasing globally, rising by 2.3 billion metric tons annually from 2014-2023, or 7 percent. However, some major emitters—like the United States and the European Union (EU)—have declining emissions. Simultaneously, those declines are overtaken by increasing emissions from other countries. Notably, several other major emitters like China, India, and Russia have rising emissions.

The United States has shown the largest emission declines from a single country: In the 10-year period from 2014-2023, the nation reduced its annual CO2 emissions by 617 million metric tons, or 11 percent. Notably, the EU plus the United Kingdom (referred to as EU-28 in emission data), which manages emissions as a bloc, saw the largest emission decline of 661 million metric tons over the 10-year period, which was a 19 percent decline.

The largest increase in CO2 emissions can be attributed to China, which increased its emissions over the same period by 1.9 billion metric tons, or 19 percent. For every metric ton of emission decline in the United States, China increased its CO2 emission by three metric tons. This illustrates how even significant progress on emissions from wealthy nations like the United States is not sufficient to alter the global trajectory of emissions.

Overall, in 2023, the largest CO2 emitters are China (31 percent), the United States (13 percent), India (8 percent), the EU-28 (7 percent), and Russia (5 percent).

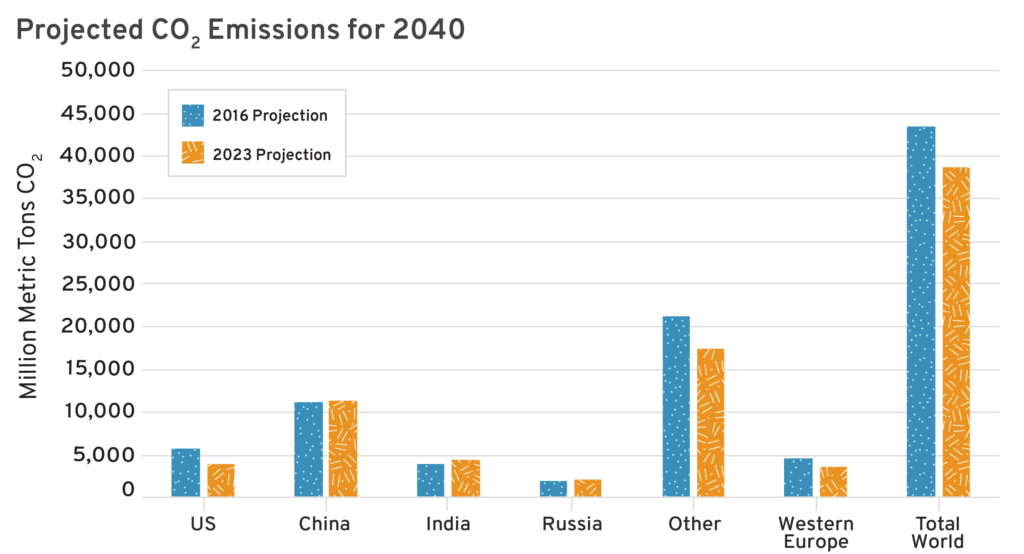

Historical emissions, though, do not give much insight into whether nations are making progress on their emissions. To compare historical data to projections, we examine the U.S. Energy Information Administration’s (EIA) International Energy Outlook (IEO) 2016 and 2023 projections for 2040. Overall, we see that despite the global rise in CO2 emissions, more recent projections show lower CO2 emission than earlier ones. We also see that the United States and Western Europe are now projected to have even lower emissions than earlier projections, while China has a worsening outlook for its future emissions.

Projection data comparison helps to illustrate the relative standing of nations and regions. For developed countries, it is fair to say that they have been making more progress on emission abatement than anticipated. For the United States, projected future annual CO2 emissions were revised downward by 1.7 billion metric tons (about 30 percent) in the 2023 IEO compared to the 2016 one. Overall the latest projection shows the U.S. CO2 emissions in 2040 will be 37 percent below its 2005 peak.

Western Europe has made similar progress, with the difference between the 2016 and 2023 IEO projections for 2040 877 million metric tons lower, or 19 percent lower.

For contrast, China’s projected CO2 emissions in 2040 under the 2023 IEO are 11.2 billion metric tons, which is 99 million metric tons higher than the 2016 IEO, or about 1 percent.

India and Russia have also had their projected CO2 emissions in 2040 revised up, with the 2023 projection showing 16 percent and 4 percent higher than the 2016 one, respectively.

Globally, fossil fuel consumption is expected to remain high

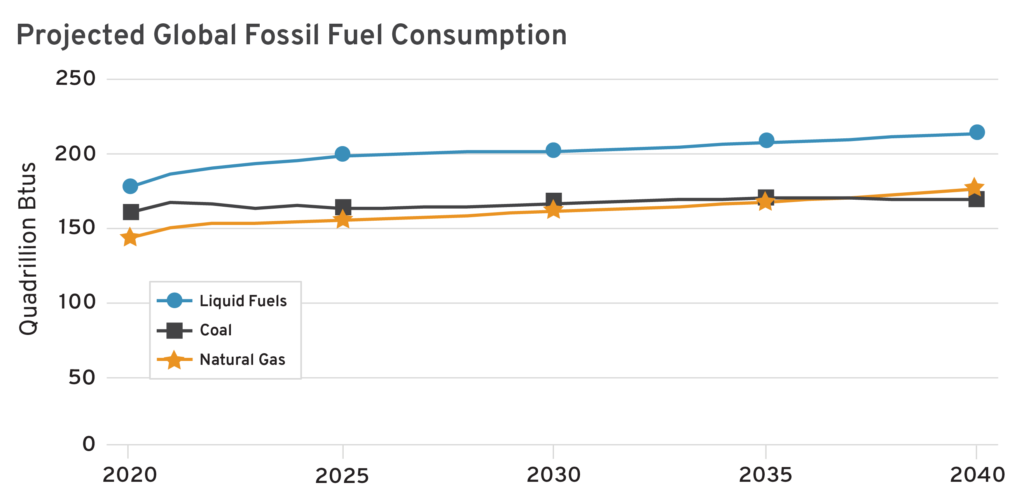

While there is considerable media focus on “net-zero emission scenarios,” such efforts do not represent anticipated reality; rather they are simply an expression of a pathway that would deliver net-zero emissions. The IEO, by contrast, is focused on the projected energy demands, and what energy resources are readily available to fulfill those demands at an affordable price. In comparing the 2016 IEO and 2023 IEO projections for 2040, we see that fossil fuels are still anticipated to be the primary energy source.

Share of Total Energy by Source 2040

| 2016 Projection | 2023 Projection | |

| Liquid fuels | 30% | 28% |

| Natural gas | 26% | 23% |

| Coal | 22% | 22% |

| Nuclear | 6% | 4% |

| Other | 16% | 23% |

| Fossil Share | 78% | 72% |

The latest IEO projects that by 2040, the world will still receive 72 percent of its energy from fossil fuels. Notably, though, this is down from the 78 percent that was projected in 2016. Compared to the 2016 IEO, the 2023 IEO projected lower fossil fuel consumption and higher alternative energy (mostly renewable energy) consumption. However, despite those revisions, overall fossil fuel consumption is expected to increase from present day levels.

Policy Insights

There are two key insights from the data that should influence U.S. foreign policy with respect to climate change. The first is that, despite U.S. emission abatement, many other major emitters have made essentially no progress in adjusting their emission trajectory. The second is that, despite renewable energy playing a growing role in global energy consumption, fossil fuels are expected to remain a predominant energy source for many years. Climate policy that ignores these issues is unlikely to alter the trajectory of global emissions.

U.S. Role in Global Emission Abatement

The overall landscape of GHG emissions is one in which the United States and other Western nations represent a shrinking share of both emission production and consumption-based emissions. Global emissions are still rising, and this is largely because developing nations have rising emissions, but most of the emission increases are explained by China’s dramatic rise in CO2 emissions. Over the 10-year period from 2014-2023, global annual CO2 emissions increased by 2.3 billion metric tons, and 1.9 billion metric tons of that increase came from China alone.

Part of the reason for this shift is an improving living standard in China, reflected in their rising consumption emissions. But from a policy lens, the troubling issue revealed in the data is that both China’s per capita and consumption-related emissions are increasing, rather than decreasing as is seen in Western nations. This indicates that China and countries with similar emissions growth are satisfying rising energy demand with higher-emitting energy sources (such as coal). This is significant because a prevailing theory of a global “energy transition” is that if the United States and other wealthy nations become early adopters of clean energy, that the rest of the world will embrace similar activities. The data, though, does not support this claim.

The more probable explanation for continued global reliance on high-emitting resources like coal (China alone accounts for approximately half the world’s coal consumption) is their low cost, and the imperfect substitutability of alternative energy sources. Variable resources like wind and solar do not easily substitute for thermal resources like coal or natural gas. In other words, market dynamics of energy cost and demand are more important determinants to global energy—and thus emission—trends than public policy posturing in wealthy nations.

Impacting the emission trajectory in nations like China, then, is likely best achieved by making lower-emitting energy sources more readily available and at lower cost. This may take the form of more natural gas supply to substitute for coal, or further developments to reduce the costs of battery storage which would make low-cost renewable energy better able to substitute for thermal resources. Focusing on reduced consumption, which is proposed by some organizations, is less likely to be embraced as such policies fail to address the demand for improved living standards globally.

From a U.S. domestic policy perspective, the global emission data paints a picture that high-cost policies focused on deployment of clean energy, such as electricity subsidies, have little impact globally. This is expected, as in economics the effect of the subsidy is to transfer the costs of clean energy from producers and consumers to taxpayers, but the subsidy does not alter the underlying incentives for productivity. Subsidies also simultaneously undercut the benefits of market competition in facilitating cost abatement. The data does not support the idea that transitioning energy costs from the private sector to taxpayers induces any reciprocal clean energy uptake in countries that either cannot afford or do not desire the cost of clean energy subsidies.

More important to altering global emission trajectories are policies that impact the fundamental, unsubsidized cost and availability of energy resources. Fossil fuels continue to dominate projected energy supply even when renewable energy is expected to be very low cost because of the limitations of renewable energy as a substitute to fossil fuels. Policy efforts focused on reducing the cost of energy storage would go further than policies that subsidize renewable energy generation in improving the outlook of renewable energy as a fossil fuel substitute.

Pro-innovation policies, and market dynamics that reward cost-reduction, are more likely to have an impact on global emissions because such policies do not require behavioral change or additional cost borne by foreign emitters that so far have been reluctant to raise their ambition for emission abatement.

Conclusion

Global emission trajectories show continued reliance on fossil fuels. Improved progress on CO2 emission abatement in wealthy, western nations like the United States is offset by rising emissions in developing nations as well as China. Domestic policies that have been focused on public support for clean energy technologies have not translated into reciprocal action in foreign countries, indicating that market dynamics of cost and resource availability are greater determinants for foreign energy consumption than U.S. public policy.

Policymakers that seek to reduce global GHG emissions should focus on efforts that are more likely to appreciably mitigate the costs of low-carbon energy sources or improve their ability to satisfy energy demand (such as if energy storage costs fall). A pro-innovation agenda is more likely to alter global emission trajectories than the current-law U.S. policy of widespread subsidy for mature clean energy technologies.