The Crime and Safety Blind Spot: Has the criminal justice system become a revolving door for repeat offenders?

This is part of the “Crime and Safety Blind Spot” series, which presents an opportunity to understand various perspectives, entertain new ones, and consider different conclusions. Read the introduction and view other posts here.

**Updated crime data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics and the Federal Bureau of Investigation has been released since the start of this series. The new figures are reflected in this post.**

INTRODUCTION

Conversations about crime and safety often center on one thing these days: repeat offenders. Some blame progressive bail reforms and “soft-on-crime” prosecutors. Others argue that the system designed to ensure safety fails to address the root causes of criminal behavior, perpetuating a cycle in and out of the institutions. This post explores various views, studies, and solutions related to repeat offenders.

| PERSPECTIVES FROM THE LEFT | PERSPECTIVES FROM THE RIGHT |

| “Automatically enhancing an individual’s sentence due to their history does not deter crime or increase public safety. These enhancements are part of California’s tough-on-crime history, which has led to our state spending more on incarceration than on higher education, overcrowding in our prison system, and devastating impacts on communities of color and those impacted by the failed war on drugs.” –Sen. Scott Wiener (D-Calif.) “So many of these crimes probably began with an addiction that led to the crimes. Treating the addiction helps us prevent the type of recidivism that we have seen in the past.” –Gov. Andy Beshear (D-Ky.) | “The resurgence of violent crimes across our state show why bail reform is a necessary approach to keep Georgia’s citizens safe. This legislation proposes aggressive bail reform focused on repeat and violent offenders and has my full support.” –Lt. Gov. Burt Jones (R-Ga.) “Across the country, surges in violent crime and deadly drugs have forced businesses to board up and working Americans to think twice about the cities where they’ve chosen to raise their families. . . .[W]hen they look for answers to this senseless violence, they find radical prosecutors refusing to do their jobs. Liberal district attorneys are watering down criminal codes and outright refusing to prosecute repeat offenders who should be behind bars.” –Sen. Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) |

EXPLORING KEY PERSPECTIVES AND BLIND SPOTS

What are repeat offender trends?

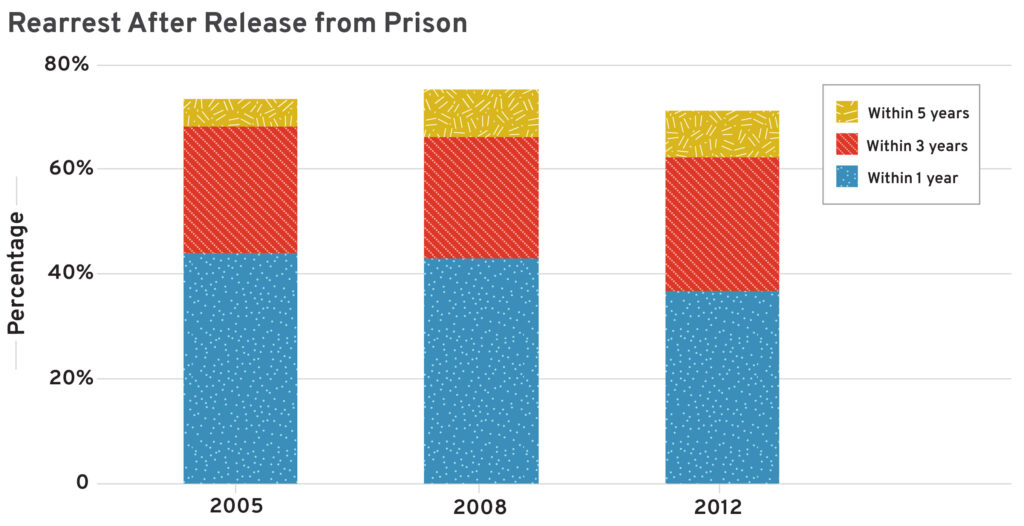

Repeat offenses are often tracked as recidivism statistics, which measure the number of convicted individuals who reoffend after being released from incarceration within a specific timeframe. More rarely, “repeat offender” can refer to individuals who reoffended while out on pretrial release. The primary challenge in tracking recidivism year-to-year lies in the need for consistent longitudinal studies, which are resource-intensive and not commonly conducted. Further, reoffense rates for pretrial release are rarely compiled or made public. The following chart provides available data to compare post-conviction recidivism trends.

| States with Highest Recidivism Rates (Return to prison after release) | States with Highest Reincarceration Costs |

| Alaska | California |

| Connecticut | Florida |

| Delaware | New York |

| Colorado | Texas |

| Hawai‛i | Illinois |

| States with Lowest Recidivism Rates (Return to prison after release) | States with Lowest Reincarceration Costs |

| Oregon | Maine |

| Texas | Wyoming |

| Oklahoma | Rhode Island |

| South Carolina | Nebraska |

| Minnesota | North Dakota |

Potential Blind Spot: Recidivism rate definitions vary by state and by study. Differences in tracking period lengths, what qualifies as a reoffense (arrest or imprisonment), and other factors can lead to drastically different statistical findings. For example, recidivism rates can miss the broader picture if they only include those entering and returning to prison and omit those who serve time in county jails, receive probation, or are rearrested or convicted without a prison sentence. How often a state uses certain forms of punishment—such as prison—can also skew the perception of local reoffense rates. Additionally, recidivism studies rarely include individuals who commit crimes while out on pretrial release.

What is the impact of repeat offenders on our criminal justice system?

- A 2014 study found that 369,200 people admitted to state prisons across 34 states had 4.2 million prior arrests, highlighting the impact repeat offenders have on police and prisons. One report estimated that states collectively spend over $8 billion annually on reincarceration.

- Studies show that most individuals released before trial successfully complete their release without rearrest, suggesting that the consequence of jail time for low-risk offenders could be an unnecessary waste of taxpayer money (although some nonviolent individuals still use excessive amounts of public safety resources).

- Research shows that people are most likely to reoffend early in their probation terms. One analysis of probation data from two states found that over 90 percent of individuals who completed a year without re-arrest could have served shorter probation terms without increasing recidivism and reduced probation officer caseloads by 32 to 44 percent.

Potential Blind Spot: When we focus on catching and reincarcerating repeat offenders, we often overlook the cycle of failure perpetuated by the system itself. Most people who go to jail or prison eventually return to their communities, yet recidivism rates remain alarmingly high under our current system. This raises several critical questions. Is incarceration working as a deterrent? Are we missing opportunities to address the root causes of criminal behavior? While the risk of reoffending is significantly lower among individuals accused of crimes and awaiting trial, how do we identify and focus resources on those most likely to pose a threat?

What factors contribute to individuals reoffending?

- A Connecticut study identified criminal history as one of the strongest predictors of recidivism, both pretrial and post-conviction. Pretrial risk assessments also frequently rely on criminal history as a key factor in determining an individual’s risk of reoffense or court nonappearance.

- A Kentucky study found that the length of pretrial detention greatly impacts recidivism among low-risk defendants. Those held 2 to 3 days were nearly 40 percent more likely to reoffend than those held for under 24 hours, and those detained over 30 days were 74 percent more likely to reoffend. A similar pattern was observed for moderate-risk defendants, while no such relationship was found in the high-risk category.

- Factors like behavioral health issues, homelessness, and unemployment make reintegration into society challenging and could increase criminality.

- One year post-release, 75 percent of those released from prison remain unemployed.

- Jail inmates are 7 to 11 times more likely to experience homelessness.

- Individuals with co-occurring substance use and mental health disorders have higher recidivism rates.

Potential Blind Spot: The disruptions caused by incarceration—such as losing a job, housing, or even custody of children—can make reintegration far more challenging and contribute to reoffense rates. This raises questions about causality: Does detention itself worsen outcomes due to job loss, family disruption, or trauma, or are there preexisting vulnerabilities among those detained longer? Risk assessments and criminal histories can help identify who may reoffend, but their accuracy is limited.

How are different strategies affecting reoffense rates?

- Voluntary programs like education, job training, and behavioral health services aim to address the root causes of criminality to reduce recidivism. Results are mixed—some research shows that secondary-degree programs can reduce recidivism by 30 percent (with greater results for postsecondary education programs), whereas job training seems to have minimal effect. Voluntary mental health support shows promise, but its success is limited among those with co-occurring substance use issues.

- Mandatory measures like supervision, therapy, or abstaining from substance use are designed to address criminal behavior and encourage participation with structured consequences for noncompliance. Research shows mixed results but highlights an increase in technical violations.

- Incapacitation reduces crime by physically preventing individuals from offending in society while confined. This is accomplished via pretrial detention; a jail or prison sentence; or the revocation of bail, probation, or parole. Although effective in the short term, it rarely provides long-term deterrence when used alone.

Potential Blind Spot: Many strategies emphasize rehabilitation or incarceration, assuming the threat of punishment or access to services after the fact will deter future offenses. However, research shows that the likelihood of apprehension and swift response are more effective deterrents than the intervention itself. Improving case clearance rates or expediting case resolutions could yield better results. Alternative strategies like restorative justice, deflection, and sealing criminal records can also reduce recidivism. Additionally, most people age out of crime. If incapacitation is considered, equipping judges with a robust number of options—both to discern risk and to evaluate alternatives to incarceration—could be more effective.

R STREET’S PERSPECTIVE

Repeat offenders are perceived as a major issue in our communities, and they expend considerable criminal justice system resources. While they may not represent the majority of justice-involved individuals, their frequent interactions with system actors often make them the focus of public frustration and policy decisions. Blame falls on specific policies (such as bail reform), but less attention is paid to understanding who is reoffending and how to break the cycle. Repeat offenders exist nationwide, not just in “progressive” states.

Detention is not a permanent solution; rehabilitation remains essential. Support programs, whether mandatory or voluntary, show varied effectiveness. Mandatory programs can provide accountability but risk harm through harsh sanctions for technical violations. Voluntary programs offer flexibility but risk lower engagement without clear incentives. A balanced approach that combines both strategies may yield better results. Even more critical, however, is prevention—identifying and supporting individuals struggling before they enter the justice system.

Repeating the same punitive responses with the same individuals and expecting different results is, to paraphrase the old saying, a form of insanity. Proactively increasing access to services, improving case processing times, solving more crimes, and strategically using detention for individuals who repeatedly ignore the law could make a greater impact. Smarter strategies—not recycled approaches—are key to reducing recidivism.