What Policymakers Should Know About the Illegal Drug Supply

The rise and proliferation of the potent synthetic opioid fentanyl across the United States over the past decade caused record overdoses—peaking at more than 110,000 in 2023. This crisis brought unprecedented attention to the contents of the nation’s illicit drug supply. A recent R Street policy study explains how prohibition affects the illicit drug supply, examines the evolving contents of the supply, and highlights key takeaways for policymakers looking to save lives.

Prohibition makes the supply more dangerous

While the fentanyl-driven overdose crisis has been extreme in numbers, it is simply the latest manifestation of an ongoing problem: Prohibition makes the drug supply more toxic and unpredictable. This is because illicit markets are inherently unregulated and thus lack quality control, while criminalization itself incentivizes increased potency and prevents transparency.

The illicit drug market lacks quality control mechanisms to guarantee products are what they claim to be and to ensure consistency of potency. Consequently, the supply is characterized by fluctuations in potency and the intentional and unintentional addition of a changing array of substances, often with unknown and unpredictable effects.

Furthermore, interdiction itself incentivizes manufacturers to produce more concentrated substances that can be moved across borders in smaller quantities to reduce the likelihood of detection. This is particularly true in the era of synthetic substances, which—when compared to plant-derived drugs—require less space and labor to produce and are far easier to tweak to create something new. These factors contributed to the emergence and proliferation of fentanyl over the last decade and are behind the recent rise of even more potent opioids and sedatives.

Because of these issues, people buying drugs on the illicit market often cannot trust the quality or safety of their supply. The lack of transparency amplifies the dangers of illicit drug consumption, as people do not know what is a safe dose or how they may be affected by unknown additives. This is exacerbated by drug seizures, which make the local supply less predictable and interfere with people’s attempts to stay safer by working with known sellers.

Drug supply changes tend to be highly localized

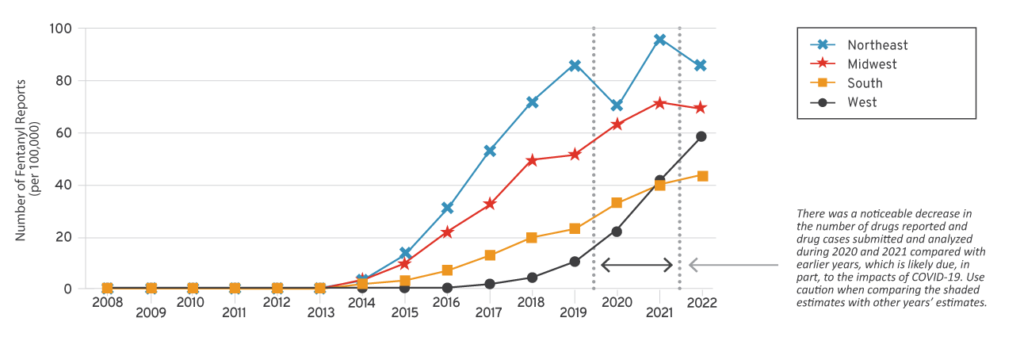

While most media coverage of the overdose crisis has focused on national numbers, the drug supply fluctuates locally. We have seen this both with the rise of fentanyl and, more recently, xylazine, which emerged on different drug markets at different times. Figure 1 shows that while fentanyl appeared in large quantities in the northeast as early as 2015, it did not hit western states hard for another four to six years.

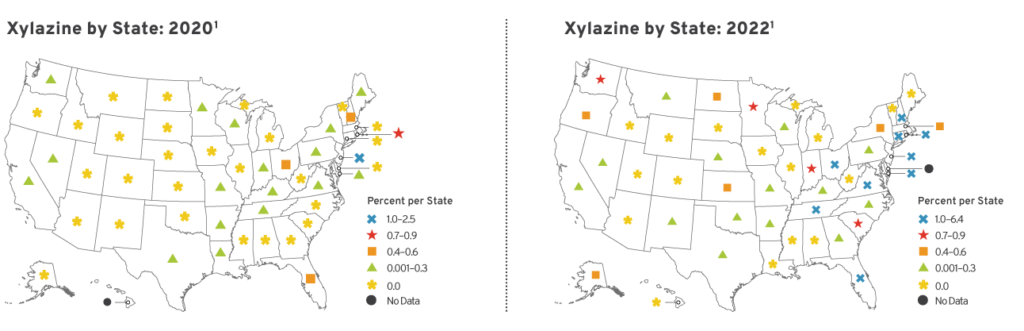

Xylazine also entered and spread throughout geographically dispersed drug markets at different times. As seen in Figure 2, the number of states reporting xylazine seizures grew drastically from 2020 to 2022.

Figure 2: Percentage of Total Drug Reports Identified as Xylazine, by State, 2020 Versus 2022

As a variety of new substances make their way into the supply—nitazines, carfentanil, bromazolam, and dexmedetomidine are among the most troubling—they will also spread across the country along distinct paths. Because of geographic variation in the supply, it is essential to rely on the local knowledge of on-the-ground experts and facilitate their tailored, flexible responses.

Public health approaches must be tailored and adaptable to save lives

Public health approaches to substance use include prevention, treatment, and harm reduction, which have proven effective in keeping people safer. For example, policies that allow distribution of drug checking equipment and the overdose reversal medication naloxone are associated with reductions in overdose fatalities. But to maximize their benefits when the drug supply is in constant flux, policies authorizing these programs must avoid being overly prescriptive or heavy-handed with their regulation. Individuals and organizations must be given freedom to tailor interventions to local needs and sufficient flexibility to adapt swiftly—for example, handing out xylazine test strips as soon as they catch wind that the drug is in their area—rather than waiting on the relatively slow pace of legislatures.

Conclusion

The illicit drug supply in the United States is perpetually in flux. Prohibition hinders quality control and transparency while incentivizing increased potency, all factors that make the supply dangerous and make it difficult for individuals to stay safe. Furthermore, changes in the market are not uniform across the country; rather, new drugs enter and proliferate geographically distinct markets at different times. Coupled with these localized changes, the market’s instability means that harm reduction and other public health interventions must have the freedom and flexibility to meet changing community needs as quickly as possible.